Introduction

In my wide-ranging survey of “Neoplatonism,” I included a section on the fourth-fifth-century Church Father Saint Augustine of Hippo. Augustine’s influence, both in the Catholic Church and across Protestant Christianity (when it arose in the early 16th century) is difficult to overstate. In fact, Augustine was one of only four early church personalities to receive the high approbation of being named a “Doctor of the Church,” in recognition “of the great advantage the whole Church has derived from their doctrine[s].”[1] It’s safe to say that Augustine, who – according to Google – was canonized by Pope Boniface VIII in 1303, was a pillar of Christian orthodoxy.

Due to this, it has struck some readers (viewers) as somewhere between odd, mistaken, or scandalous for me to have seemingly enrolled him among the ranks of “the Neoplatonists.”

For example, one commenter stated (in part): “…I am not …certain that as many Church Fathers as you have listed were of a Neoplatonic orientation. The occult may claim them as their own but many times that is an advertising gimmick. In the case of Augustine I dispute the notion that he was a Neoplatonist. He was an implacable foe of Hermes and Hermeticism, which are inseparable from Platonism. (The “Tractatus” attributed to him is apocryphal). The occultists deceitfully claim him for their own, predicated on trifles – because he did not deny the intellectual capacity of Plato, for example; which is a tribute to Augustine’s prudence and probity. In his masterwork, “City of God Against the Pagans” (the last three words of the title are often omitted in the modern era) – for example in Book IX chapter XVI – he clearly distinguishes between Christianity and Plato. Furthermore, Augustine rejected the Renaissance Neoplatonic appeal to the pagan philosophers as forerunners who bore witness to the validity of Christianity.”[2]

First of all, thank you so much for reading and commenting! Admittedly, in the article and in the companion video, I may not have adequately distinguished Augustinianism from (Plotinian) Neoplatonism. Once properly distinguished, however, I’d still argue that what we have – with St. Augustine – is a species of Christian Platonism. So, let’s dive in; I’ll try harder to make that case.

For a video version of (most of) this essay, see HERE.

Background

Recall that I started off the original video with a summary of some major tenets of Neoplatonism – especially as it was formulated by some of its ancient framers. Please see – or see again! – that presentation for the full story.

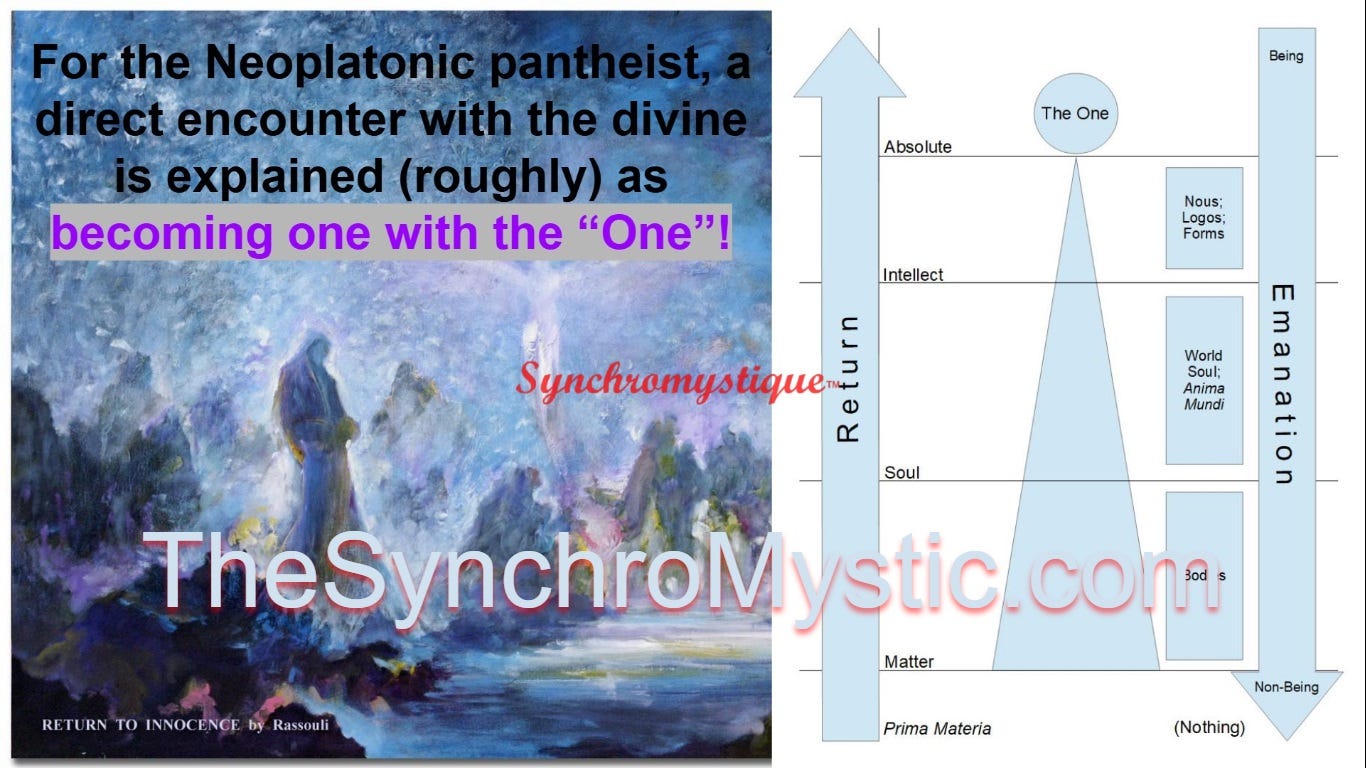

But, to aid comprehension here, and as a refresher, I listed five (5) main doctrines. (1) Neoplatonism’s view that the world is a hierarchy of entities with “something” called the “One” at the top. (2) Neoplatonism’s doctrine of emanation, according to which all other realities emerge from the One. (3) Neoplatonism’s pantheism, that is to say, it’s near identification of the divine with the entire universe. (4) Neoplatonism’s related mysticism – or its preoccupation with the idea that human souls ought to strive to ascend to and reunite with the One. And (5) Neoplatonism’s tendency towards syncretism, which is the tendency to try to harmonize or combine ideas from competing religious and philosophical systems.

Let me say, right off the bat and for the record, that I never meant to imply that Saint Augustine was a Neoplatonist in the sense of advocating or subscribing to these five doctrines. I tried to caveat the Augustine material in the original presentation. But, I now realize that I guess I never gave a direct disclaimer (as I just have).

Of the Neoplatonic varieties that accept the five basic beliefs sketched above, I think a case can be made that many (or even most) are heavily (possibly inextricably) wedded to Hermeticism. Although the occult-leaning journalist Jason Louv described “Hermeticism, Neoplatonism, and operative magic” as “three distinct yet intertwining schools of thought”.[3] And I basically agree with that.

Regardless, I don’t think, and have no interest in arguing, that Augustine was a Hermeticist in any meaningful sense. I’m going to kick the topic of Hermeticism into an “Afterword.” (Q.v.)

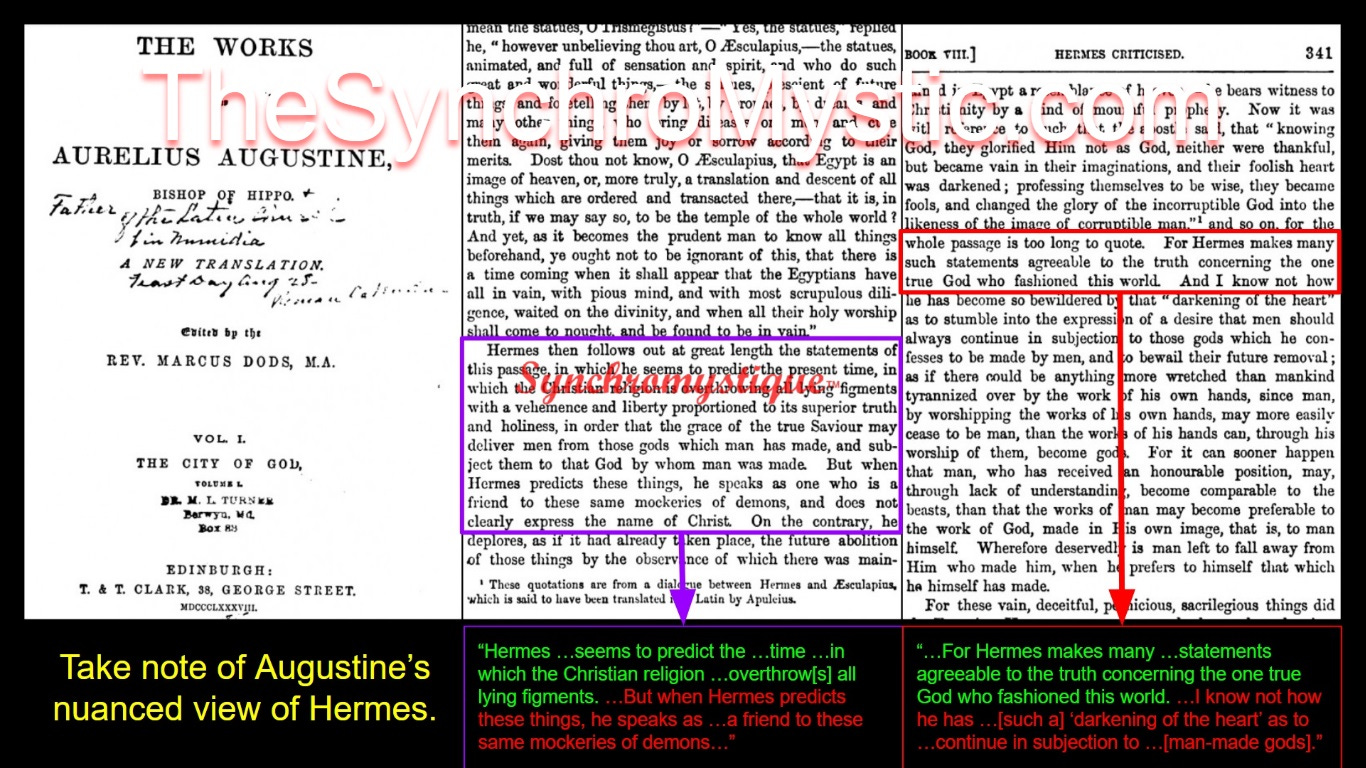

Here, I will note the remarks of Egyptologist Ronaldo Pereira, who listed Augustine among those “[o]ther writers” – also including Arnobius, Cyril of Alexandria, Lactantius, and Tertullian – “who discussed Hermetic literature [e.g., the Ad Asclepius, or Logos Teleios, tractate] and thereby helped shape its reception…”.[4]

Of course, it’s one thing to read and discuss Hermetic texts, and help “shape [their] reception,” and it’s another thing to endorse the texts’ worldview. The Church Fathers, including Augustine, “…rejected [the Hermetica’s] Paganism, but [they] noted that similarities could be found within their theology. …[Many] early Christian Fathers went as far as to quote the Hermetic texts in their campaign against heresies.”[5]

Before I use the occasion of the comment to unpack further details about Plato, the Platonic-Neoplatonic legacy, and Augustinianism, I’ll try to answer the most pressing question. If Augustine didn’t hold any of the distinctive, Neoplatonic beliefs (the One, emanation, pantheism, mysticism, syncretism), then why did I feature him in the Neoplatonism presentation at all?

Terminological Troubles

There are several reasons. Firstly, Augustine was (some kind of) a Platonist. And Platonism and Neoplatonism are often treated together.

Indeed, as I believe that I mentioned in my opening remarks to the “Deep Dive Into Neoplatonism” presentation, there’s arguably an inconsistency in the literature about how to refer to Plato’s multifaceted intellectual heirs. Sometimes Platonism and Neoplatonism are distinguished; other times, they’re used synonymously. This does give rise to confusion.[6]

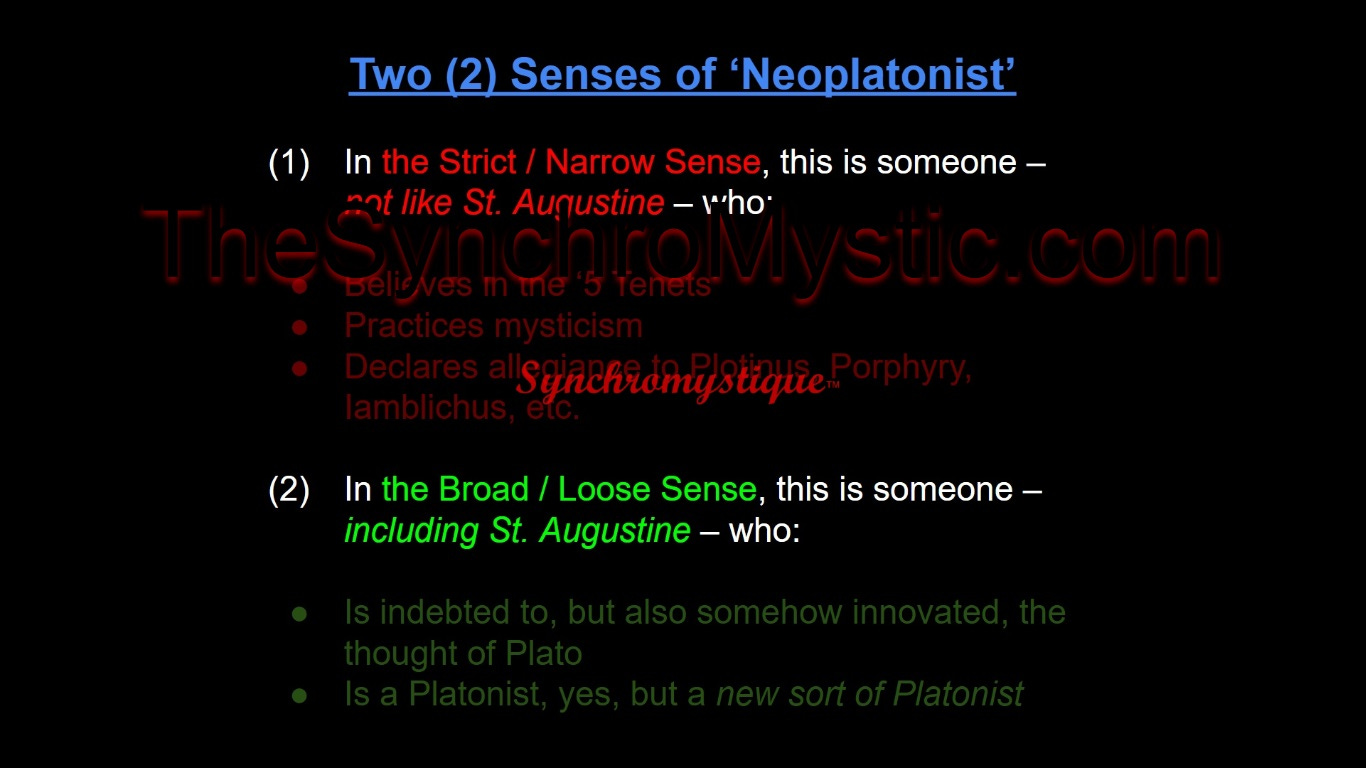

I suggest that there are two (2) senses of “Neoplatonism.” One is technical.

On this narrow use, a thinker counts as “Neoplatonic” if and only if he was a disciple of Plotinus, practices mysticism, and upholds the five tenets. So… not Augustine.

Then again, note well that Plato himself wasn’t a Neoplatonist in this sense, either historically or ideologically![7] This may seem too obvious to mention, but we should carefully distinguish Plato from his Neoplatonic descendants. This is to say that subsequent thinkers – Plotinus, Porphyry, Iamblichus, Proclus, etc. – embellished (and even mystified) Plato’s thought and took it in new directions (e.g., toward metaphysical monism and religious pantheism).

Secondly, a distinction between Plato and Neoplatonists is important because it's doubtful that Augustine read Plato’s (Greek) dialogues directly. Rather, Augustine encountered Plato via various Neoplatonists, chiefly, Plotinus and Porphyry.[8] But going back to the question of terms…

If we insist on (what I earlier called) a “strict use” of Neoplatonism, where Neoplatonists are all and only those who are Pantheists, syncretists, and so on, then we should equally recognize that the word Platonism marks off the pre-Plotinian, non-mystical philosophy of Plato himself.

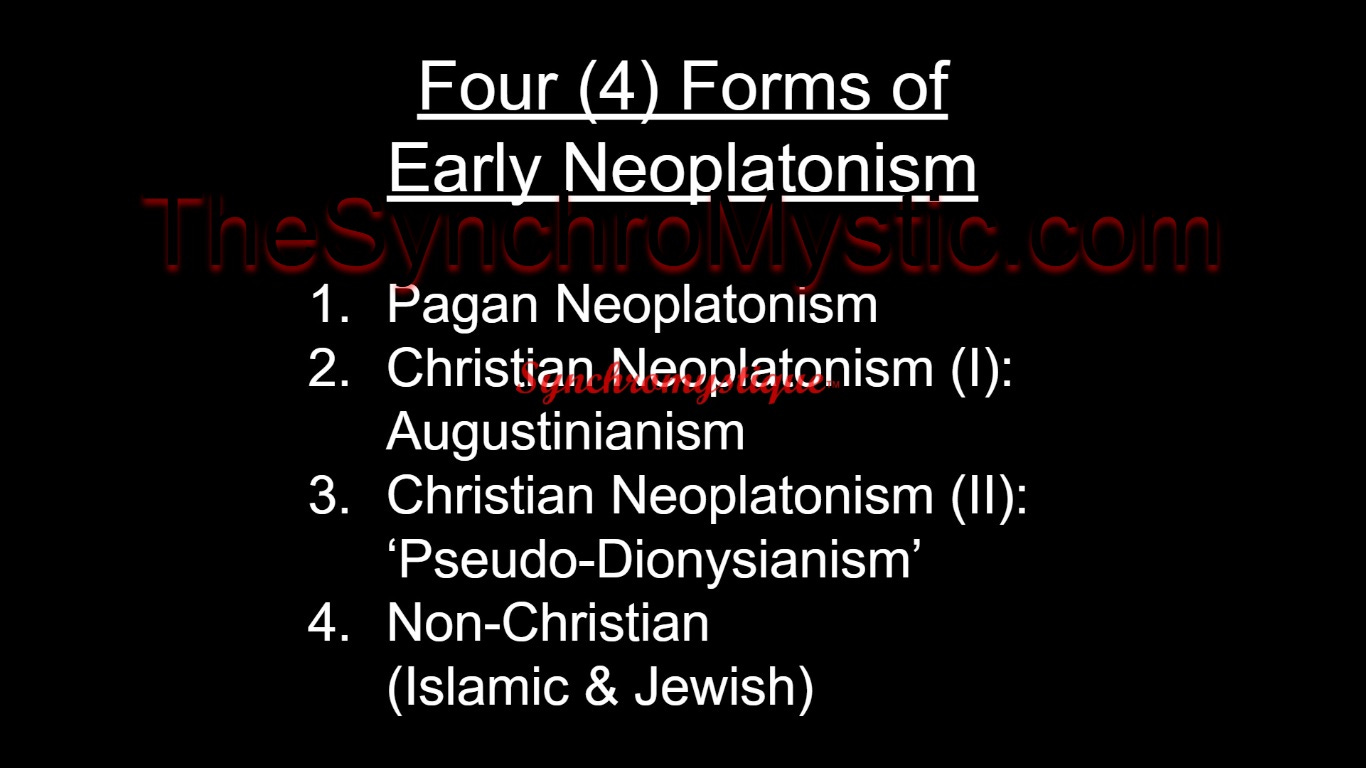

A second use of “Neoplatonism” is broader. A thinker is “Neoplatonic” in this looser sense if they’re indebted to Plato, no matter how. Most of the major “Neoplatonists” in this broad sense have put some novel “spin” on the doctrines they inherited from Plato. In fact, one of the main points that I was trying to suggest in my original presentation was that, in my opinion, Neoplatonism – in this looser sense – can be thought of as coming in subvarieties: Neoplatonisms (plural), if you like. Sticking to ancient Neoplatonism, the subcategories that I enumerated were the following.

(1) Pagan, Anti-Christian Neoplatonism (especially of a type modeled on Iamblichus),

(2) Christian Neoplatonism (of an Augustinian type),

(3) Neoplatonic Christianity (of a Dionysian type – later dominant in the Renaissance), &

(4) Non-Christian Neoplatonism (of other sorts, such as Islamic, Judaic, etc.).

In this broad sense, Neoplatonism isn’t always “Hermetic.” We’ve got to take systems and thinkers on a case-by-case basis. Plotinus would still be a Neoplatonist – as would Iamblichus. And Iamblichus would also be a Hermeticist. But Augustine was a non-Hermetic Neoplatonist of a Christian variety, and certainly not a Hermeticist. Pseudo-Dionysius was a different sort of Christian Neoplatonist, one who was much more Hermetic. That’s the sort of thing I had in mind.

We probably do need to make an initial terminological decision about which way we want to talk.

If we allow for a loose way of speaking (and I’m willing to allow it), then “Broad Neoplatonism”[9] can refer to the entire spectrum of thought that is, in some sense, “Platonic” (more on that later).

However, if we want to, we certainly can reserve the term “Neoplatonism” for the Hermetic line that arguably started with Ammonius Saccas and Plotinus, and proceeded through Iamblichus, Proclus, Dionysius, and so on, ultimately gaining traction (in supposedly Christian circles) during the Renaissance. I don’t prefer this way of speaking because I think it blurs the lines among subtypes that I’d rather distinguish: Such as Pagan Neoplatonism and Neoplatonic Christianity.

At the same time, I don’t want to argue about words. You’re free to choose whatever terms you think best. But, whatever word you pick, it’s best to stick to it. And I might have fumbled the ball a bit on this score.

If we do opt for the narrower usage, then what I previously called “Christian Neoplatonism” has to be renamed. Not to worry: The literature is replete with alternatives. We could call the variant Augustinianism, Augustinian Platonism, Christian Platonism, or whatever. For this exploration, I pick Augustinianism.

One More Preliminary Wrinkle

But the Neoplatonists’ elaborations were far from the only interpretations of Plato in play. This should be uncontroversial. It’s worth recalling that there was a little-mentioned intermediate period, called “Middle Platonism,”[10] during which there were similar (though opposing) shifts in interpreting Plato’s thought – this time towards metaphysical dualism and religious Gnosticism.

In this, Plato’s thought was seminal. Firstly, Plato distinguishes a world of Particulars from a world of Forms. This distinction was Plato’s answer to perennial philosophical problems such as “the one and the many” and the dichotomy of change and permanence. How do we perceive reality as a unified whole when it appears to be made up of a diversity and plurality of individual things? Is nothing actually permanent, as Heraclitus thought? Is change an illusion, as Parmenides and Zeno evidently held?

Plato’s solution to these puzzles was to posit two different realms. One of these, the perceptible world of everyday experience, was the realm of becoming, of change and of plurality; the other, an imperceptible realm of Forms, was unified and permanent.[11]

This spills over into what you might call Plato’s cognitive dualism of perception, on the one hand, and conception, on the other. This is to say that we explore the world of Particulars with our five senses. But the world of Forms can only be “conceived of” or explored with the mind. This bifurcation further unfolds into Plato’s anthropological dualism. According to this, we humans are composites of two kinds of “stuff”: material bodies and immaterial souls.[12]

Finally, from the standpoint of the theory of knowledge (or epistemology), there’s a major dualism between changing, time-and-space-bound opinion – which is the best we can hope for when we base judgments on the deliverances of perception – and timeless, unchanging knowledge – which, to Plato, has to be grounded in the Forms.

These nested dualisms suggest a strong connexion between Plato and the later Gnostics. Some “scholars have even referred to Gnosticism as a kind of Platonism.”[13] This association is underscored by the fact that Gnostics sometimes labeled the god of Darkness (the creator of what they call “evil matter”) after Plato’s “Demiurge.”[14] We’ll talk more about all this in a minute.

Was Augustine a Platonist?

Let’s start with this. Augustine was deeply (if indirectly) influenced by Plato. So, yes, he seems pretty clearly to have been a “Platonist.” Commentators with diverse worldviews agree on this.

For example, the late 20th-c. British philosophy “popularizer” and television-show host Bryan Edgar Magee, a self-professed religious “agnostic,”[15] concisely described St. Augustine’s thinking as: “The Fusion of Platonism and Christianity.”[16]

Magee, despite being ideologically opposed, nevertheless echoes the language of 19th-20th-c. French Jesuit theologian Eugène Portalié, who likewise described the bishop’s worldview as “…the fusion of Platonic philosophy with revealed dogmas…”.[17]

Similarly, Philology Professor Christian Tornau, writing in the standard reference, the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, says that “…Platonism in particular …[was] a decisive ingredient of …[Augustine’s] thought.”[18]

Finally, 20th-c. American Reformed theologian and philosophy professor Ronald Herman Nash – although espousing a quite different worldview from Magee, Portalié, and (I presume) Tornau – nevertheless also wrote that Augustine’s “work is …a model for those …thinkers who would use Platonism as a framework for their Christian world-and-life view.”[19]

As far as I can tell, Magee, Nash, Portalié, and Tornau are not occultists in any sense.

So, what were they thinking of when they all classified Augustine the same way? We’ll look at several things. As we do, bear in mind that, despite the fact that Augustine drew heavily from Plato – via Neoplatonists such as Plotinus – he felt at liberty, or even compelled, to modify his sources. Augustine did this out of “faithfulness to the Christian Scriptures and [out of] his own genius.”[20]

In places such as On the City of God Against the Pagans, or, The City of God, Augustine wrote clearly and voluminously against such forms of paganism as “the popular cults of Isis, Mithra and Cybele…”.[21] We can confidently say that, “[o]n any issue where Plotinus’s thought and Scripture were irreconcilable, Augustine parted company with Plotinus and sided with the Bible.”[22] The same goes for Augustine’s treatment of Plato – with the only caveat that, due to his indirect access to Plato, Augustine would’ve had difficulty demarcating Plato from Plotinus.

Why Would Augustine Have Wanted to Be a ‘Platonist’?

As to why Augustine attempted to combine Platonism with Christianity at all, and thought it was permissible to do so, Magee gives plausible suggestions. He wrote: “One thing that made it possible for Augustine to fuse the Platonic tradition in philosophy with Christianity is the fact that Christianity is not, in itself, a philosophy. It’s fundamental beliefs are …historical rather than …philosophical…: for instance, that a God made our world, and then came to live in the world of his creation as one of the people in it, and appeared on earth as a man called Jesus, in a particular part of Palestine, at a particular time, and lived a life that took a certain course, of which we possess historical records. Being a Christian involves, among other things, believing such things as this, and trying to live in the way …God …told us, partly through the mouth of …Jesus… Jesus did …provide …moral instruction, but he was not much given to discussing philosophical questions [per se].

“So it wasn’t the case that there was a Platonic philosophy on the one hand, and on the other, a philosophy at variance with it, [called] Christian philosophy – thus giving Augustine the problem of marrying the two. …[R]ather …Augustine, believing that Platonic philosophy embodied important truths …that the Bible did not concern itself with, wanted Platonism to be absorbed into the Christian world-view.”[23] That’s one reason. Another is a fondness for the man, Plato.

Plato as a ‘Christian Before Christ’

As noted in the “Deep Dive Into Neoplatonism” video, the 2nd-c. Christian apologist and philosopher “…Justin [Martyr called] Socrates and Plato, along with [the Old Testament Patriarch] Abraham, …‘Christians before Christ,’ because they followed the Divine Reason within them.”[24]

Especially from the standpoint of someone who takes Christian revelation seriously, there are numerous issues with Platonism. Later on, we’ll briefly catalog some of these. But it’s worth thinking about why early Christians felt such an affinity with or devotion to Plato or to Platonism – as that sort of friendly sentiment Justin Martyr expressed.[25]

Many reasons for this come from Plato’s writings. Consider a provocative passage, in Plato’s Republic (362a). The character Glaucon explains that, if ever the world were to encounter a truly just man, that man would end up being “crucified.”

Doubtless, some overzealous apologists make excessive claims for this text – such as that it was a bona fide prophecy. Still, it’s enough (for us) that it shows Plato’s remarkably Christian-sounding moral sensitivities.[26]

To some early Church Fathers, “both Greek philosophy and the Old Testament were preparatory phases that found their culmination in Christianity.”[27]

We can’t forget that Plato put a premium on evaluative notions like Beauty, Goodness, Justice, and Truth. Not all of Plato’s contemporaries had the same sensibilities. The Sophists didn’t!

Besides arraying himself against Sophism, Plato also opposed Hedonism, materialism, naturalism, relativism, and skepticism. Later thinkers would mobilize the resources of Platonism against other “-isms” such as atheism, empiricism, and mechanism.[28] Christians also frequently oppose these ideologies.

The upshot is this: “…Platonism is saturated with many of the same metaphysical assumptions as Christianity, revealing a deep concord between these two seemingly incompatible schools of thought. …Much like the Christian God, Plato’s form of the Good is a divine source of being for all of the world. …Just as the Christian God is truth and goodness himself, the Platonic Forms are the ultimate source of ‘truth and understanding’ for all things…According to Platonist anthropology, humans are inherently spiritual creatures possessing both a material body and an immaterial soul. …Both Platonism and Christianity understand the human soul as naturally calibrated for pursuing questions of the divine.”[29] And so on.

And, of course, in the centuries-long debate over the way to resolve the Problem of Universals, Plato was “an all-flags-flying Realist,” to borrow the colorful phraseology of philosopher John Cuddeback. Indeed, Plato was the wellspring and primary articulator of Realism. Anyone opposed to the other major position – Nominalism – ought to see Plato as some kind of ally.[30]

As an aside, nominalist thinkers such as the Franciscan friar William of Ockham, along with seminal “and radical empiricis[ts]” like fellow Franciscan Roger Bacon, “helped support the growing movement of mysticism” in the so-called “Late Middle Ages” (roughly A.D. 1300 to 1500).[31] I would also argue, although I won’t do so, presently, that – besides a connexion to this proto-empirical strand of medieval mysticism[32] (a strand that paved the road for its Renaissance successors) – nominalism is also detectable behind key theological principles that motivated the “Protestant Reformation” – including, most importantly, Sola Scriptura (or the “Bible Alone”). I’ll have to tackle all that another time.

For now, concerning St. Augustine, here’s my argument. Augustine was first and foremost a Christian. Augustinianism is a unique and thoroughgoing formulation of Christianity. If he had to choose between leading a hearer to Christian orthodoxy or convincing a reader of some arcane metaphysical contention of Platonism, I’d wager that he’d had chosen the former – without hesitation. For all that, however, Augustine’s considered, mature, complete, Christian worldview may be justifiably classified as a species of Platonism.

“The object of his philosophy …[was] to give authority the support of reasons, and ‘for him the great authority …is the authority of Christ’; and if he loves the Platonists, it is because he counts on finding among them interpretations always in harmony with his faith.”[33]

Now, at last, let’s look at some of the evidence for these claims.

Augustine on the ‘Immortality of the Soul’

An outstanding illustration of Augustine’s adherence to Platonism – by way of Neoplatonists such as Plotinus and Porphyry – was his commitment to the existence and Immortality of the Soul (the latter being the title, incidentally, of his treatise written around A.D. 387).[34]

By the way, the basics of Plato’s argument for the immortality of the soul can be put like this. To destroy something (like a glass water pitcher, for example) is to break it into parts. But, to Plato, the soul hasn’t got any parts. (It’s “simple.”) Therefore, the soul cannot be destroyed.[35]

As Fr. Frederick Copleston noted: Plato’s “…dualistic conception [of the soul] reappears in Neo-Platonism [sic], in St. Augustine, in [René] Descartes, etc.”[36] Augustine wrote: “…[A]mong those things which are created by God, …the rational soul …surpasses all; and it is nearer to God when it is pure.”[37] Not to put too fine a point on it, but “[i]n his anthropology[,] Augustine was firmly Platonist, insisting on the soul’s superiority to and independence of the body.”[38]

One could – not unfairly – think of this as a combination of (or a meditation on) the Platonic idea of the indestructibility of the soul, the Neoplatonic association of individual souls with the World Soul (mentioned in the “Deep Dive” video), and portions of the New Testament. In the Gospel of Matthew (chapter 10, verse 28), we read: “Do not be afraid of those who kill the body but cannot kill the soul. …[B]e afraid of the One who can destroy both soul and body in hell.”[39] Now…

If taken as a piece of serious metaphysics, as opposed to (say) a metaphor, Matthew 10:28 may be said to imply two (2) things: Firstly, that there is a soul and, secondly, that God is the only being capable of destroying it (since, apart from His activity, the soul is otherwise immortal).[40]

Other arguments for the bare existence of the soul, from people like Plato and (later) Descartes, turn on a point that is now known as the “Indiscernibility of identicals.” This principle states that if two things are identical, then they are also indiscernible – i.e., they have all the same properties.

So, then, Descartes points out, if I can doubt the existence of my body, but I cannot doubt the existence of my mind (because, cogito; ergo, sum), then my body and my mind do not have all the same properties. (He seems to be thinking of bodies as having a property like “being able to be doubted,” while souls have the property “being unable to be doubted.”) But if they don’t share all the same properties, then they’re not identical.[41]

Finally, (substance) dualism – of body and soul – is suggested to some thinkers on the basis of pure introspection. “For example, Plato, Augustine, Descartes, [Joseph] Butler, and [Thomas] Reid [all] held to [a view called] S[ubstance]D[ualism] in virtue of being aware of themselves from the first-person perspective as not reducible or identical to their bod[ies].”[42]

This is “cashed out” in terms of a consideration called intentionality or “aboutness.” “The property of intentionality is the property of being about something or being of something. For example, [William Lane Craig says,] I can think about my summer vacation or I can think of my wife. [But, p]hysical objects don’t have these sorts of properties. The brain is not about something any more than a chair or a table is about something …[O]nly thoughts which are of something that have this kind of aboutness …to [them]. But on [the] view [that] …there is no soul …[where] instead you just have the brain …intentionality is …an illusion. …This leads a naturalist philosopher like Alex Rosenberg to …[say] that we never really think about anything. It is just an illusion that we have intentional states.”[43] Granted, Rosenberg is an atheist. But…

Let’s say you’re thinking: A lot of traditions believe in some kind of “soul.” How does that show Augustine was a Platonist?

Well, apart from the details of his intellectual formation, which clearly suggest that he was steeped in the “books of the Platonists,”[44] we can come at the point in a backhanded way by looking at the argument of Plato’s critics.

I have in mind the “anti-soul movement” represented by Anglican bishop and New Testament scholar Nicholas Thomas “N. T.” Wright. Wright is part of a small and diverse group of Christians who are understood as “rejecting the soul” as a theological concept.[45] For Wright’s part, he criticizes modern advocates of body-soul “dualism”[46] on several grounds, one of which is his view that, “when Paul and the gospels use the word psyche, it is clear [to him] that …[that the] biblical authors] are not using it in the sense we’d find in Plato or [the Judaic-Platonist] Philo”.[47]

When Wright turns his attention to Christian exegesis, he asserts that “what the great tradition from Augustine onwards was referring to with [respect to certain words, like justification and soul] is significantly different from what Paul was referring to when he used the word[s].”[48] Thus Wright objects to a Platonizing of St. Paul, and seems to associate aspects of that sort of maneuver with Augustine. But…

Contrary to Wright, Augustine evidently believed that an immortal soul – in Plato’s sense – was not only what St. Paul had in mind, but was also further reason to commend Plato’s perspicacity (and similarity to Christians).

Even if Plato is the source of Augustine’s arguments for the soul and its immortality, as seems barely short of a certainty, note that Augustine crucially altered the picture. To Plato and Pagan Neoplatonists, the soul and its immortality were related to transmigration. Souls “reincarnate.”[49] Following the Bible, Augustine rejected this notion.[50] E.g., in the Book of Hebrews, the first part of verse 27, in chapter 9, tells us that “it is appointed for man to die once” – not over and over.

Augustine was a Realist About ‘Forms’

An even bigger connexion between Augustinianism and Platonism was the former’s allegiance to the latter’s doctrine of Forms. To put it slightly differently, Augustine believed in the real existence – independently of particular things – of what Plato called Forms or Ideas, and what later came to be termed “Universals.”[51] Forms make particular things, like my neighbor’s dog, the kinds of things they are. Fido is a dog because Fido “participates” in the Form of Dog-ness

Since I unpacked this a bit more in the “Deep-Dive” video, I won’t devote a lot of space to it, here. Suffice it to say that, if we tried to identify Platonism’s philosophical “core,” we’d be hard-pressed to do better than to name Plato’s notion of an abstract, immaterial, non-physical, perfect, spaceless, timeless, unchanging realm of Forms that not only exists, but constitute true reality. The Forms lie beyond, and make possible, our ephemeral experiences and perceptions of the physical world. Physical objects are merely imperfect approximations, copies, echoes, or shadows of the Forms. The Forms also ground truth claims and make knowledge possible.

A realist argues like this. For a sentence like “this stop sign is red” to be true, there has to be such a thing as the stop sign, there has to be such a thing as redness, and the two entities – the stop sign and the redness – have to be related in the correct way. A realist might say that the stop sign exemplifies or instantiates redness. Stop signs are no problem – they’re run-of-the-mill particular objects. But, redness? What’s that? Well… the realist says redness is a “universal.” For our purposes, we’ll say redness is one of Plato’s Forms. And the stop sign participates in it.

To a Platonist, more important Forms lie behind judgments such as equivalence, similarity, and identity. This comes across in the dialogue Phædo (esp. 74b-76c), where Plato argues that we conclude that two things are “equal” because we have the concept of “equivalence” already in our minds. To Plato, we don’t derive that concept from the world. Rather, we recognize when the world presents us with equal things, because deep down we already know what “the equal” is.

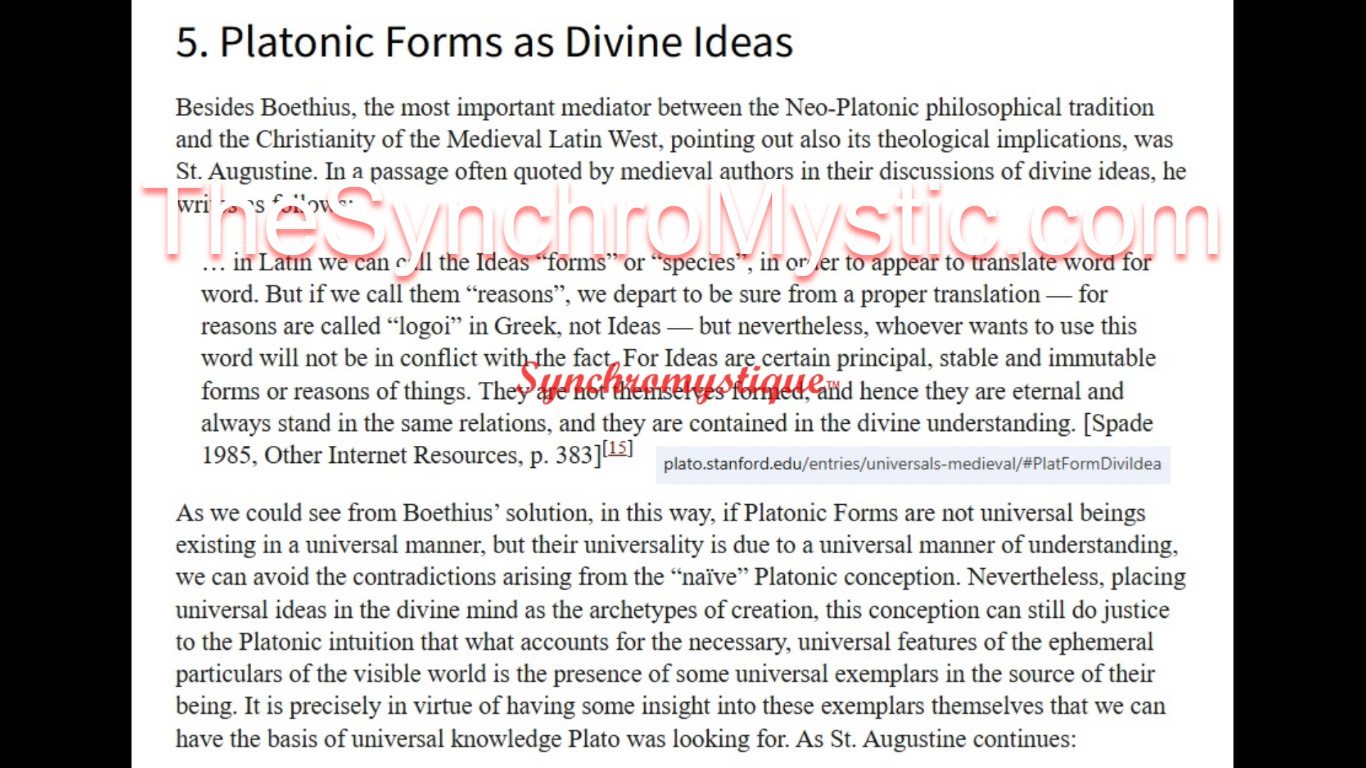

Augustine agreed with Plato’s general picture. He held: “[T]here are certain principal forms of ideas, or stable and unchangeable aspects of things, which are not themselves formed, and [which] are …eternal and always …[exist] in the same way… [These ideas] …neither arise nor perish; … however, …everything that arises and perishes, is said to be formed [with them].”[52]

Augustine seems to be saying that changeable, perishable, temporal things depend upon unchanging, nonperishable, and eternal things. To punctuate the connexion with Platonism, he wrote: “Plato called these principal aspects of things Ideas: but they are not only ideas, they are Truths themselves, because they are eternal, and remain such and unchangeable…”.[53]

Surely, a thinker who assents to the core of Platonism qualifies as a Platonist. QED.

Nevertheless, Augustine makes a crucial change, saying of the Forms, not that they subsist in some “Platonic Heaven,” as Plato held, but that they’re “…contained in the divine intelligence.”[54]

Changes like this gave Augustinianism longevity in Christian circles because they mitigated the elements of Plato that were incompatible with Christianity. Some 800 years later, for example, St. Thomas Aquinas was favorably “quot[ing] Augustine as to the …[Divine] Ideas…”.[55]

That’s saying something, for Aquinas leaned heavily toward Aristotle. In fact, that was a bone of contention between Aquinas and Bonaventure. The latter believed that Aristotelianism and Christianity were irreconcilable and he recommended going back to Augustine’s Platonism![56]

We shouldn’t forget to add to these resemblances the qualified praise that Augustine gave to Platonists. In The City of God, the second of Augustine’s two major works (the first being his autobiographical Confessions), he says of “the Platonists” (in Chapter 5): “Their Opinions [are] Preferable to Those of All Other Philosophers,” going so far as to say that “none come nearer to us [Christians] than [do] the Platonists.”[57]

Augustine then describes “Platonic philosophers” as among those “who …recognized the true God as the author of all things, the source of the light of truth, and the bountiful bestower of all blessedness.”[58] He commends Platonists as “great acknowledgers of so great a God” for not “having their mind[s] enslaved to their bod[ies],” thereby “suppos[ing] the principles of all things to be material” in the manner of materialists like Thales (whose central belief is often glossed as all is water), Anaximenes (all is air), the Stoics (all is fire), or Epicurus (all is atoms and the void).

His point is: Like Christians, Platonists have a healthy respect for the spiritual, over and above the physical. Both “…Plato and the Scriptures agree that our souls have a special affinity to God, that we are morally responsible for our actions, and that there is a time of reckoning in the world to come.”[59]

When navigating this terrain, we do need to keep in mind that Augustine expressed antipathy to “Hermetic” Neoplatonism – or, what I called “Magical Neoplatonism” in the “Deep Dive” video.

In fact, there was an ongoing rhetorical war between Neoplatonists like Iamblichus, and his school, and Christian polemicists like Tertullian and Augustine.

The former “attacked [Christian views] on magic, [and] accus[ed] Christians of impiety for denying the divine principles supporting theurgy”.[60] Additionally, “…Neoplatonists …vehemently protest[ed] against the …Christian dogma that human salvation has already been accomplished vicariously through the life and death of a man revered as the son of god. …[For some of them,] the route to salvation …[was] the philosophic life, a sincere and arduous effort of the mind to return to the One and forever abrogate any concerns for the body.”[61] Others based their hopes on a more magical-mystical form of “ascent” that I distinguished from Augustinian mysticism.[62]

For his part, Augustine does have room in his system for a sort of “ascent of the soul.” But, for Augustine, such is an intellectual movement. For the soul that becomes attuned to God, the contemplated “ascent” is a gradual turning one one’s attention from earthly matters to divine matters.[63] It’s not taken metaphysically – as an attempt to “(re-)unite” your being with the One.

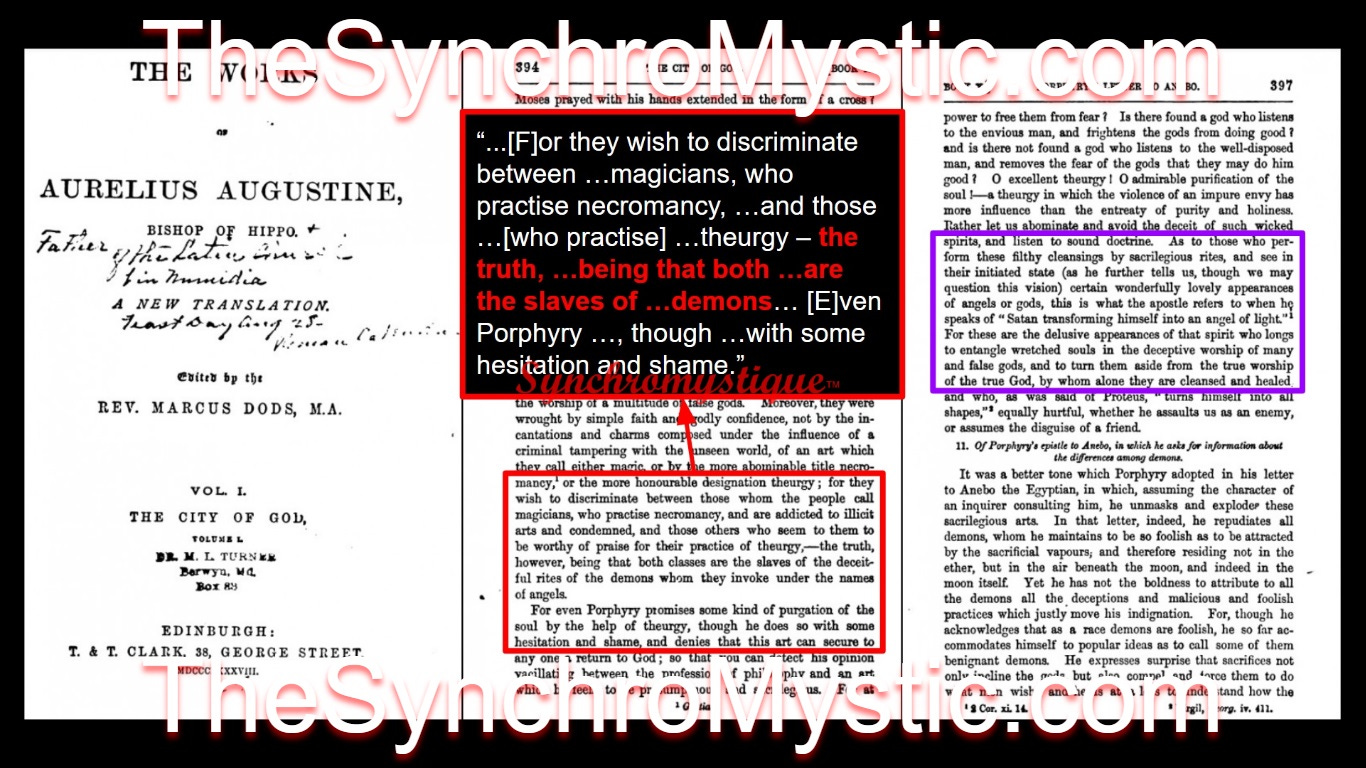

Augustine has dire warnings for those seeking to force a reconciliation with God through magic. Augustine harshly condemned both necromancy and Porphyry’s Neoplatonic “theurgy” as “…the deceitful rites of …demons” that are tantamount to “criminal tampering with the unseen world”.[64]

Nevertheless, it would be a mistake to conclude that Augustine took nothing onboard from Neoplatonism. It was not for nothing that Plotinus’s “name was so dear to …St. Augustine,” as the late Catholic philosopher and Jesuit Fr. Frederick Copleston once put it.[65] For, at the very least, as we have said, it was “[t]hrough the Neo-Platonists [that] Platonism made its influence felt on St. Augustine and on the formative period of mediæval thought. …The Augustinian philosophy was, through Neo-Platonism, strongly impregnated with the thought of Plato.”[66]

We just sketched that latter association, So, now, let me say something specifically about Augustine’s intellectual debt to Neoplatonism. I gestured to some of this in my previous video.

How Was Augustine Influenced by Neoplatonism?

Let me prime the pump for this section by opening with Augustine’s own words. In his biography, Confessions, he wrote: “[God] procured for me …certain books of the Platonists, translated from Greek into Latin. And therein I read, not indeed in the same words, but to the selfsame effect, enforced by many and various reasons, that, In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. …”.[67] Here is Saint Augustine telling us that he thinks that he’s found an echo of the Gospel in the “books of the Platonists.” That’s quite remarkable.

Of course, Augustine quotes one scripture passage after another. He alternately declares, of some Christian doctrines, that he does find them in the “books of the Platonists”; whereas, for other doctrines (such as believing in the name of Jesus), he says: “This I did not read there.”[68]

So, Augustine’s handling of “the Platonists” (really, as stated, the Neoplatonists Plotinus and Porphyry) is nuanced. But Augustine is by no means dead set against anything smacking of “Platonism.” Therefore, we have to look more closely at Augustine’s system. When we do so, I think, we won’t fail to find substantial overlap between Augustine’s thinking and Neoplatonism.

Neoplatonic-Inspired Account of Evil

For example, in the previous video, we discussed Augustine’s “privation” account of “evil.” In this account, Good exists, but evil – strictly speaking – does not. “Evil” is just a word for the absence of Good. But you can make the case that Augustine’s account, here, owes more to Neoplatonic than directly Platonic influences. Before I explain how, let’s get a handle on Augustine’s idea.

In the “Deep-Dive” video, I suggested that you can get a quick “fix” on his notion by thinking of our commonplace understanding of light. The difference between a well-lit room and dark room isn’t that the former is filled with stuff called “light” whereas the latter is filled with some opposing stuff called “darkness.” Instead, we say that the dark room merely has no light. Light has being; darkness does not. So it is with Good and evil, according to Augustine. And, remember…

Augustine wasn’t just waxing philosophical. He was arguing against a competing belief system known as Manichæism,[69] to which he had previously subscribed. Augustine’s fascination with Manichæism was partially motivated by his desire to find a satisfactory solution to the “Problem of Evil,” that is” “[t]he problem of reconciling the imperfect world with the goodness of God.”[70]

The Manichee solution was to posit the existence of two gods, Good and Darkness, who were locked in perpetual war. Thus, Manichæism advanced a version of Gnostic, theological dualism.

“That’s all well and good,” you’re saying. But how does this help show that Augustine’s privation account of evil was inspired by Neoplatonism?

Well, think of it this way: Plato wrote his dialogues and then he died.[71] One of the first formal schools to follow him was what is now called “Middle Platonism.”[72] The salient point is that these Middle Platonists pioneered the dualistic interpretation. Major streams of Gnosticism,[73] which preceded Neoplatonism, were heavily influenced by this teaching. And “Platonic dualism” was eventually embraced by Manichæism.[74] Augustine’s departure from its ranks also marked his turn away from this sort of dualism.[75]

So, from where was Augustine inspired to articulate a monistic account of evil? It wasn’t from Gnosticism or Middle Platonism. And as stated, the earliest non-skeptical interpreters took it for granted that Plato taught dualism.

Only two groups were really toying with monism. One was the Stoics – and they were hardcore materialists. The other – of course – were the Neoplatonists.

Plotinian Neoplatonism tended toward monism. We know that Augustine was reading Plotinus and Porphyry anyway. So, just speaking about Augustine’s personal history, Neoplatonism is a pretty good candidate for his source. When we think about Neoplatonism’s beliefs, it clinches it.

Recall that Plotinus imbued his all-important (and singularly lofty) entity – the “One” – with unsurpassed Being and Goodness. All subsidiary entities emerged out of (or “emanated from”) the One. But, as derivative beings emerged, they also degraded – both in Being and Goodness. Consequently, entities at the bottom of this existential totem pole (or “Chain of Being”), such as our bodies and other material things, literally verge on non-being and evil. Now…

You don’t have to “buy into” any of the hierarchical metaphysics. Just notice the punchline. I’ll say it again, if you missed it. For the Neoplatonists, evil was joined at the hip with non-being.

I don’t know about you, but the fact that evil had little-to-no existence in the Neoplatonic picture seems awfully similar to Augustine’s view that evil is a privation of good.

Let me toss in a brief comment about a possible misunderstanding that some people might have regarding what Augustine is saying. The idea that “evil is a privation” can sound a lot like the claim that “there’s no such thing as evil,” with the consequence that evil can’t or won’t be a part of our day-to-day experiences. But, it doesn’t take five seconds to stub your toe or watch the nightly news and recognize that our world is inundated with evil.

So, realize that, in none of these cases – whether of evil, or darkness, or the Neoplatonists’ concept of the dregs of emanation – are we prevented from experiencing or perceiving the things in question. If you have trouble seeing this (no pun intended), here’s an illustration.

Visualize a pothole-covered street.

Do you usually say that the street is made of two different things: asphalt (or whatever), on the one hand, and “potholes,” on the other? No, “pothole” is just our shorthand way of referring to a gap in the asphalt. The holes are places where asphalt is broken or missing. Yet, the fact that “holes” don’t have any separate, positive existence does not safeguard your ankle if you accidentally step in one – or your tire if you drive over one![76]

Neoplatonic-Inspired ‘Illumination’

A second major example is Augustine’s doctrine of “Divine Illumination,” according to which human knowledge of the Forms (which recall are, for Augustine, the Divine Ideas) would be impossible without God’s direct and immanent assistance.[77]

Augustine gives this analogy. Just as “eye of the flesh” requires “bodily (physical) light to see, so too does “the intellectual mind” require a Divine, “incorporeal light of a unique kind”.[78]

Consider that the Gospel of John,[79] calls Jesus Christ: “The true light that gives light to everyone…”.[80] Now, it is certainly true that alchemists may be inclined to count this passage as evidence that “matter contains a light or an invisible fire whose nature is that of the Word who created Light on the first Day.”[81] But this virtual pantheism isn’t what Augustine has in mind.

To Augustine, a personal God “illumines” the minds of all people – at least, to the extent that they recognize any truth at all. By this intentional action, the Christian God guarantees the universality of knowledge by (for example) causing a priori truths to “[arise] within the soul.”[82]

A lot of this sounds like Plato himself, until you realize that, for Plato, humans know the Forms by “Recollection” (Anamnesis). For Plato, preëxistent souls inhabit the realm of the Forms, where we are able to grasp truths implicitly. Augustine rejects this entire explanation (see further on).[83]

For Augustine, humans are capable of knowledge because God implants innate ideas in our souls – not necessarily as fully formed objects of thought, but at least as mental dispositions.

However, God does not merely accomplish this once-and-for-all. Rather, He continuously informs and sustains our intellects. This is roughly what is meant by Divine Illumination.[84]

Neoplatonic-Inspired Anthropology

Recall that Augustine once held a strain of Manichæism. Like typical Gnostics, Manichees distinguished a spiritual world of goodness and light from a material world of darkness and evil.

To Mani and his followers, for a soul to become embodied, enfleshed, or incarnated was tantamount to something inherently good – a soul – being implicated in something intrinsically evil – a body. But, of course, for Augustine, a soul becoming embodied isn’t, ipso facto, a “Fall.”

In the Book of Genesis, chapter 1, verse 31, the Bible says that “God saw everything that he had made” – the physical universe and everything in it – and declared “it was very good.” The Fall is the result of sin, i.e., disordered priorities (placing the self over God) and selfish choices.

So the Gnostic-Manichee story about the inherently evil nature of flesh would no longer do.

According to the late Fordham University professor and Jesuit Robert J. O’Connell, when Augustine renounced Manichæism, he “…adopted [a] Plotinian anthropology [instead. On this Neoplatonic view,] …man is a soul fallen into …[a] body in consequence of some sin [that he] committed in his pre-existent state.”[85]

But, as we’ll discuss more fully in a minute, Augustine eventually rejected the idea of the preëxistence of the soul. So, as we’re by now hopefully accustomed to expecting, Augustine modified Plotinus’s idea of a “pre-existent” Fall.

Following the 2nd-c. Greek Bishop Irenæus of Lyon – and, we should quickly add – in line with the creation account in the Old Testament Book of Genesis, Augustine attributed the fall to Adam’s “original sin.”

So, while Augustine doesn’t say that you and I personally sinned in our own preëxistent states, he nonetheless attributes our inherited, sinful dispositions to the sin of the first man and woman – both of whom “preëxisted” us. It appears to have been an ingenious adaptation of Plotinus.

Historically, Augustine’s “...important doctrines,” in this regard, “emerge[d] in the …controversy with the …Pelagian heresy, against which …Augustine affirm[ed] the reality of the Fall and of original sin as the hereditary moral disease that we all bear, only curable by God’s grace.”[86]

A number of proposals have been advanced to explain, justify, and understand this claimed link between Adam’s sin and our inherited guilt. These include: (1) postulating Adam as the “federal head” of humanity, whose decisions, like those of the federal head of the United States (the president) have consequences for everyone under the relevant “jurisdiction”; and (2) suggesting a “modal defense,” drawing on the apparatus of “possible worlds” to suppose that, in a world where you or I had been the first humans instead of Adam, we would have sinned just as he did.

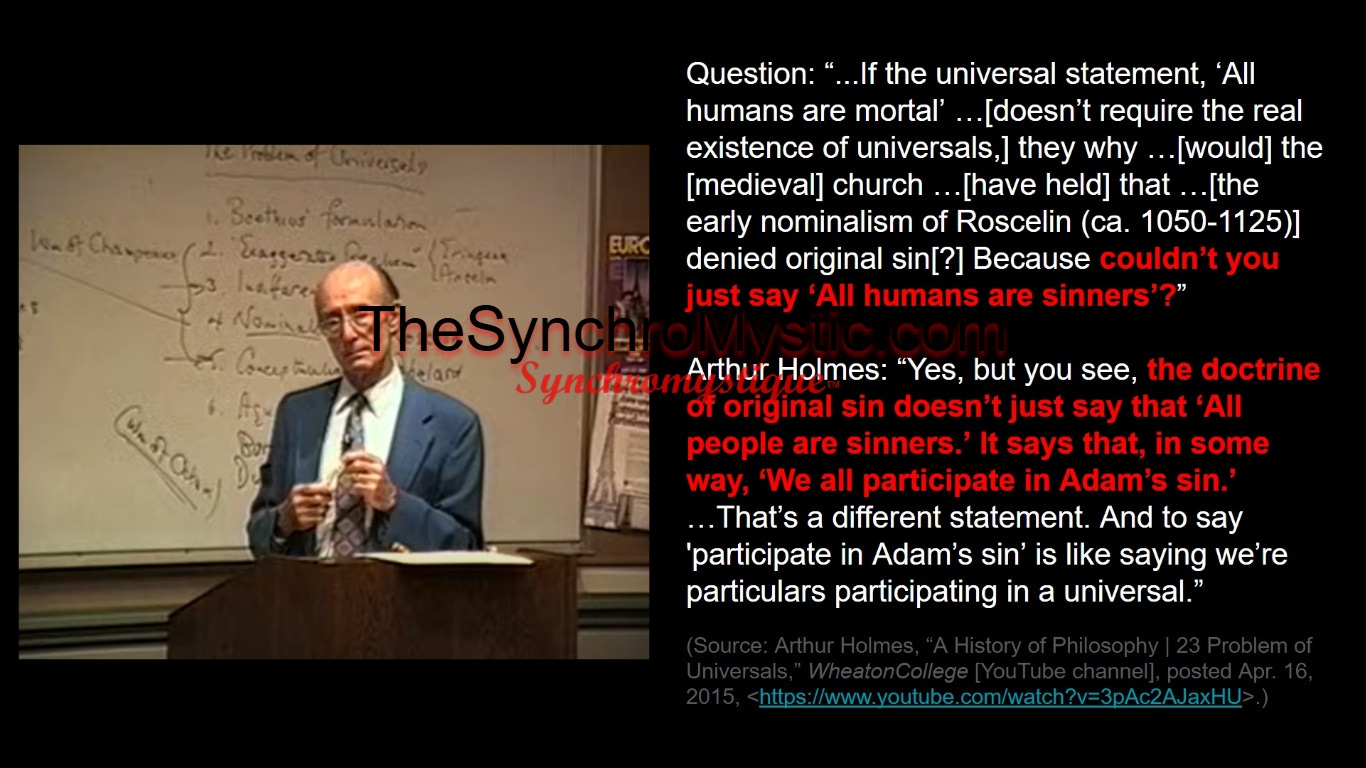

Today, it’s not uncommon to see the doctrines reduced to aphorisms such as that humans have a “propensity to evil.”[87] But, until the ascendance of nominalism, around the fourteenth century, believers in the doctrines of the Fall and Original Sin analyzed them using the resources of realism. They weren’t simply affirmations of the fact that “we have all sinned and fall short of the glory of God,” to quote St. Paul.[88]

Instead, the doctrine of original sin posited that all humans participate in the sin of Adam – where “participation,” you’ll remember, was one of the Platonist’s words for the relationship between a particular and its Universal.[89]

‘Trinity’ of the One, the Logos & the World Soul

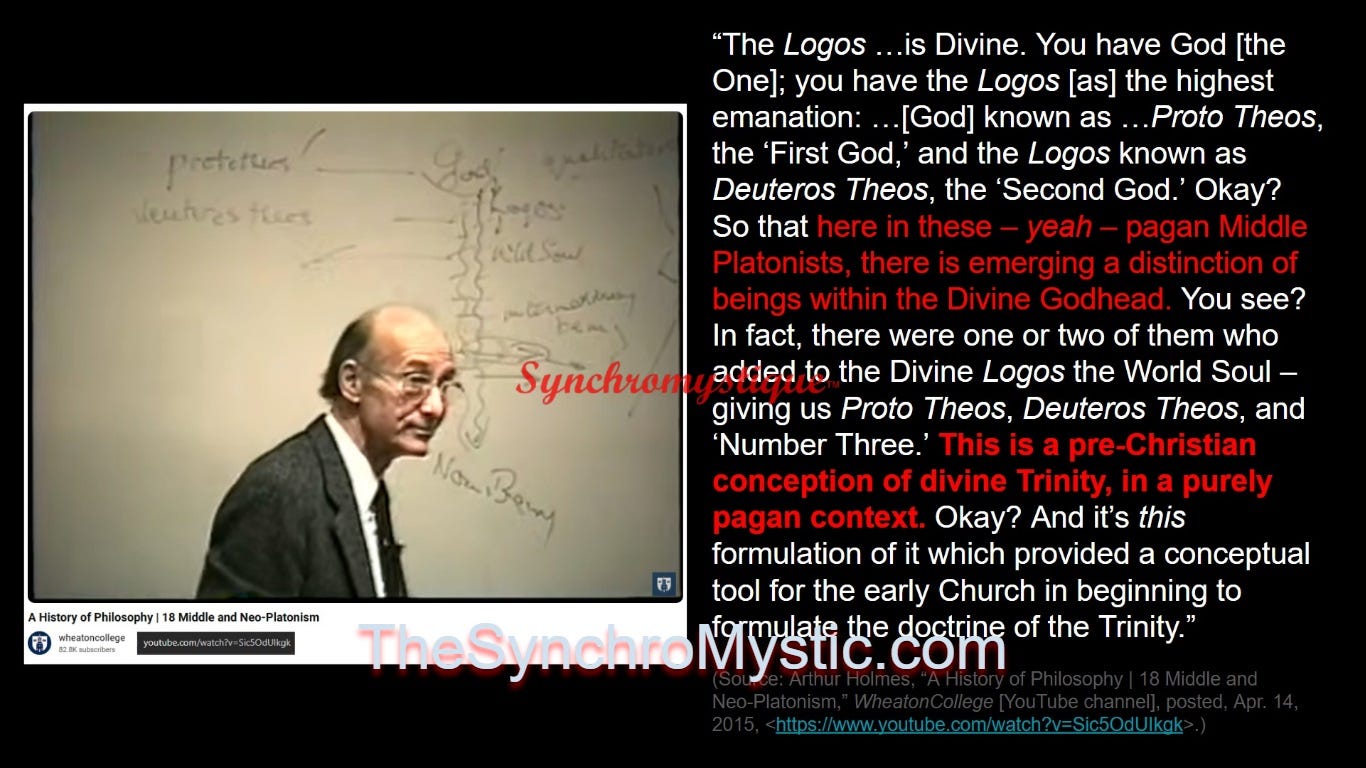

In the Encyclopedia Britannica, Arthur Hilary “A. H.” Armstrong and Henry J. Blumenthal gave a further example that they say shows “the most distinctive influence of [explicitly] Plotinian Neoplatonism on Augustine’s thinking about God …[namely,] his Trinitarian theology.”[90]

The controversial and difficult idea that Christian Trinitarianism itself might have been, well… let’s say anticipated by Neoplatonism was once helpfully (and non-technically) somewhere summarized by the late Evangelical-Protestant philosopher Arthur Frank Holmes.

In the Neoplatonic picture, Absolute reality is an indefinable, spaceless, timeless “something” known as the One. (For more, see – once again – our “Deep Dive.”)

Subsidiary reality “emanates” or “streams” out of the One as light radiates from the sun. Holmes noted that the two “highest” of these “emanations” are the Logos and the World Soul.[91] From here, in the Neoplatonic hierarchy, individual souls and the rest of the perceptible universe arise.

Without getting too deep in the weeds, Holmes suggested that the close linkage between the One, the Logos, and the World Soul – in the Neoplatonic schema – has points of contact with (and may have informed the articulation of) the Christian Trinity of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

To motivate this note, firstly, that the Apostle John literally referred to Jesus as “the Logos” in the prologue to the Gospel that bears his name. John 1:1 reads, in Koine Greek: En archē ên ho lógos, kaì ho lógos ên pròs tòn theón, kaì theòs ên ho lógos.[92] “In the beginning was the Logos [usually[93] transl. ‘the Word’], and the Logos was with God, and the Logos was God.”

Or consider a portion of the Nicene Creed, recited during typical Sunday Catholic Masses, where the Holy Spirit is said — emanation-like — to “[proceed] from the Father and the Son.”[94] Finally…

Think of typical doctrines (held by many Christians) – such as the “indwelling of the Holy Spirit.” According to this, the Spirit “lives within” Christians, aiding (or even guaranteeing) their ultimate salvation. This underscores the Holy Spirit’s intimate connection with individual souls – a connection reminiscent of that which the World Soul has with particular souls in Neoplatonism.

Pantheism Replaced By ‘Omnipresence’

A final example, cut from similar cloth as the one just surveyed, is the manifestly pantheistic and admittedly paradoxical part-whole relation that exists between the One and the universe in the Neoplatonic picture. This is to say that, to the textbook Neoplatonist, god is the universe; the One is all.

As O’Connell puts it: “…it …[takes] a firm effort of will to exclude association” of this background information with “Augustine’s thinking on God and on His relation to the world,” which thinking – ultimately – issued in the Christian doctrine of God’s “Omnipresence.”[95]

Of course, Augustine once again caveats and qualifies his doctrine. He said: “Although in speaking of him we say that God is everywhere present, we must resist carnal ideas and withdraw our mind from our bodily senses, and not imagine that God is distributed through all things by a sort of extension of size, as earth or water or air or light are distributed.”[96]

The idea of God’s omnipresence is difficult on its own. One problem partially stems from the inherent tension in reconciling the concept of God’s transcendence – or the idea that God is above, beyond, and distinct from His creation – with God’s immanence – or the conviction that God is available, “not far from us” (Acts 17:27), and is somehow “present” in all aspects of His creation.

Multiple models have been proposed to explain God’s omnipresence. The aim, here, is not to survey them. We’re simply noting that some commentators find similarities between the doctrine of omnipresence and Neoplatonic pantheism. However, we hasten to add that readers (or viewers!) must guard against the misimpression that the two ideas are equivalent. We’re not asserting that they are. Christians, especially, have been keen to draw out the differences.[97]

Problems With Platonism

Of course, despite his qualified embrace of some key Platonic doctrines, it would be misleading to say “Augustine was a Platonist,” full stop. After all, he was, more than anything, a Christian!

And this was partly because he did not find Platonism to be a completely satisfying worldview. “What Augustine did not find in the books of the Platonists were things essential to redeeming the times. What Augustine did not find in the books of the Platonists and had to find in Christian revelation was a personal God who was a God of justice, but not an immaterial form; a God of love who would listen to prayers and respond; a God of history who entered into history to redeem it, not a God who remained blissfully apart.”[98]

Whether for Augustine in the 4th-5th centuries, or for Christians today, “[n]either …[Plato nor Aristotle] can be accepted precisely as he stands…”.[99] Aquinas saw this in the latter case.

In developing his system of Aristotelian-Christianity, what we now think of as Thomism, the Angelic Doctor modified Aristotle. In this, St. Thomas followed the example of his illustrious predecessor, St. Augustine. As I hope I’ve adequately shown, Augustine likewise modified Plato and the Neoplatonists whenever he believed that fidelity to Biblical revelation demanded it.

The aforementioned late Calvinist-Baptist Ronald Nash went so far as to describe Platonism as a convenient set of errors against which Augustine painted an alternative picture. Nash goes too far, I think. But, from a Christian point of view, there’s no question that Platonism has issues.

Not least is the woolliness of Plato’s conception of God. It’s not obvious if Plato thought of his Demiurge as God, or whether he reserved the title for his Form of the Good …or something else.[100]

Commentators line up on both sides of that question, with Gnostics and Neoplatonists (not to mention Middle Platonists and Neopythagoreans) trying to incorporate both constructions (the Demiurge and the Good or the One) into their own, often convoluted, emanationist hierarchies.

For Augustine, of course, God is none other than the Holy Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, as revealed within the Christian Bible. Moreover, the Biblical God is personal, not Neoplatonism’s impersonal, unkowable “One.” The Christian God is not only personal and knowable, He who “hast formed us for [Him]self, and our hearts are restless till they find rest in [Him].”[101]

Furthermore, the Biblical God the author of “salvation history,” which has events unfolding over time, in a linear fashion, towards a conclusion (the eschaton, or “last things”). Platonists, on the other hand, generally advanced a cyclical view of history where events repeat ad infinitum.

But other problems arise with Plato’s main doctrines as well.

The Forms Threaten Divine Aseity

Another major issue with Platonism is that the Platonic Forms, understood as Plato conceived of them, are a threat to the classical theistic picture that predicates of God such properties as His aseity and (unique) necessity.[102] “Aseity,” here, refers to the idea that the Christian God is radically independent and self-existent. Specifically, He doesn’t depend on anything outside Himself for his existence. (“Necessity,” as it’s come to be modeled by possible-world semantics, analyzes the claim ‘God couldn’t have failed to exist’ as: God exists in all possible worlds.)

As Evangelical thinker William Lane Craig puts it: “Central to classical theism is the conception of God as the sole ultimate reality, the Creator of all things apart from Himself. This doctrine receives its most significant challenge from Platonism, the view that there are uncreated abstract objects, such as numbers, sets, propositions, and so forth. According to Platonism there is a host of objects, indeed, infinities of infinities of beings, which are just as eternal, necessary, and uncreated as God. So God is not the sole ultimate reality.”[103]

Of course, Augustine saw this problem. This is the reason why he situated the Forms inside the mind of God, instead of outside of Him.

In a recent paper, Craig sketched a range of Platonic alternatives, which we will not rehearse, except to say that the one closest to Augustinianism seems to be the position he calls “Divine Conceptualism.”[104] According to this, “…putative abstract objects like propositions, properties, possible worlds, and mathematical objects are, or are analyzable in terms of, God’s thoughts of various sorts.”[105] Craig lists[106] Brian Leftow, Alvin Plantinga, and Greg Welty as contemporary defenders of this position, showing that this tenet of Augustinianism has yet to run out of steam.

Preëxistent Matter Threatens Divine Aseity

Similarly, Plato has no doctrine of Creation, as Augustine came to understand it. To be sure, in his dialogue Timæus, Plato imagines that the universe had been crafted out of preëxistent matter (the “receptacle”) by a benevolent demigod figure called the “Demiurge.”[107]

As to the Demiurge’s moral character, “Timaeus describes …[it] as unreservedly benevolent, and hence desirous of a world as good as possible. [But t]he world remains imperfect, however, because the Demiurge created the world out of a chaotic, indeterminate non-being.”[108]

Just a word on terminology. To the ancient Greeks, the word cosmos implies order. Structure is “baked into” a cosmos. Our universe is a cosmos because it is law-governed and rational. The opposite of this is chaos. Chaos is inherently disordered, irrational, unstructured, and so on.

But, to Augustine, an independently existing material “receptacle” – chaotic or not – is no more compatible with the God of the Bible than were independently existing Forms. So, once again, following the lead of the Book of Genesis – where it says, “In the beginning, God created the heavens and earth.”[109] – Augustine modifies Plato. Instead of holding that the universe was fashioned out of preëxisting stuff (ex materia), Augustine articulates the unique, Christian idea of creatio ex nihilo. This is to say that God created the universe out of nothing.[110]

Here’s a crude analogy. Think of the Demiurge as having helped himself to an assortment of preëxisting stuff, like a LEGO aficionado with a box of bricks that hasn’t yet been assembled. The ancient Greek picture, inherited and embellished by Plato, was that the Demiurge took a formless chaos – like a jumble of LEGO pieces – and imbued it with order and structure using the Forms – like a person building a toy castle, with a photograph as her guide or model.[111]

But, even in an unassembled heap, the prefabricated and standardized LEGO blocks exhibit a (fairly high) degree of (incipient) structure. In our analogy, the Demiurge takes full advantage of preëxisting material – material that has the (latent) potential to be shaped into a comos – just as the LEGO pieces have the (latent) potential to be put together into a castle.

But, the God of the Bible doesn’t have to rely on any supposed and externally existing material propensities.

This point is colorfully, but (I think) persuasively, expressed through the joke about the scientist who boasted to God that he could replicate what God had done in Genesis 2:7, where it says: “The Lord God took some dirt from the ground and made a man.” So, God said to the scientist: “Show me.” The scientist smugly accepted and immediately bent over to pick up a handful of soil. But God stopped him, saying: “Oh, no you don’t. Get your own dirt!”

Carl Sagan, of all people, underscored this when he quipped: “If you wish to make an apple pie [entirely and truly] from scratch, you must first invent the universe.”[112]

Preëxistent Souls & Reincarnation Are Unbiblical

Anything that coexists with the biblical God, or preëxists His creation – such as eternal matter or independently existing Forms – is ruled out of court. That includes preëxistent souls.[113]

For Plato,[114] souls are eternal, intrinsically immortal, preëxistent, uncreated (at least, in the sense of having been created out of nothing), and even quasi-Divine.[115] Before a person’s birth, their soul resided in the realm of Forms. And, after death, the soul returns to that “Intellectual” or “Intelligible” realm. In this purely “spiritual” state, souls have direct, perfect awareness of the Forms. However, after an indeterminate amount of time,[116] they are – for various reasons that needn’t detain us (and are, in any event, not quite clear[117]) – “reincarnated” into another body.[118]

As already mentioned – both earlier in this video, as well as in the “Deep Dive” – the New Testament Book of Hebrews (9:27) seems to exclude the possibility of reincarnation.

But Augustine also rejected Emanationism as an explanation of the origin of the soul. This had been proposed by the monist and Neoplatonist Plotinus and was also propounded, in a different form, by “gnostic-manichaean dualism”.[119]

You may remember from the “Deep Dive” presentation that Neoplatonic Emanationism is also bound up with Pantheism, or the idea that – literally – “all is god.” Augustine explicitly eschewed this emanationist-pantheist system, writing: “The soul is not a part of God; for if it were then it would be in every respect unchangeable and indestructible.”[120]

According to the 20th-c. Roman Catholic theologian Ludwig Ott, Augustine’s favored view on the soul’s origin – in line with his overall theological orientation – is what is known as “Creationism,” or the idea that: “Every individual soul was immediately created out of nothing by God.”[121]

Is Sense Experience Reliable Or Isn’t it?

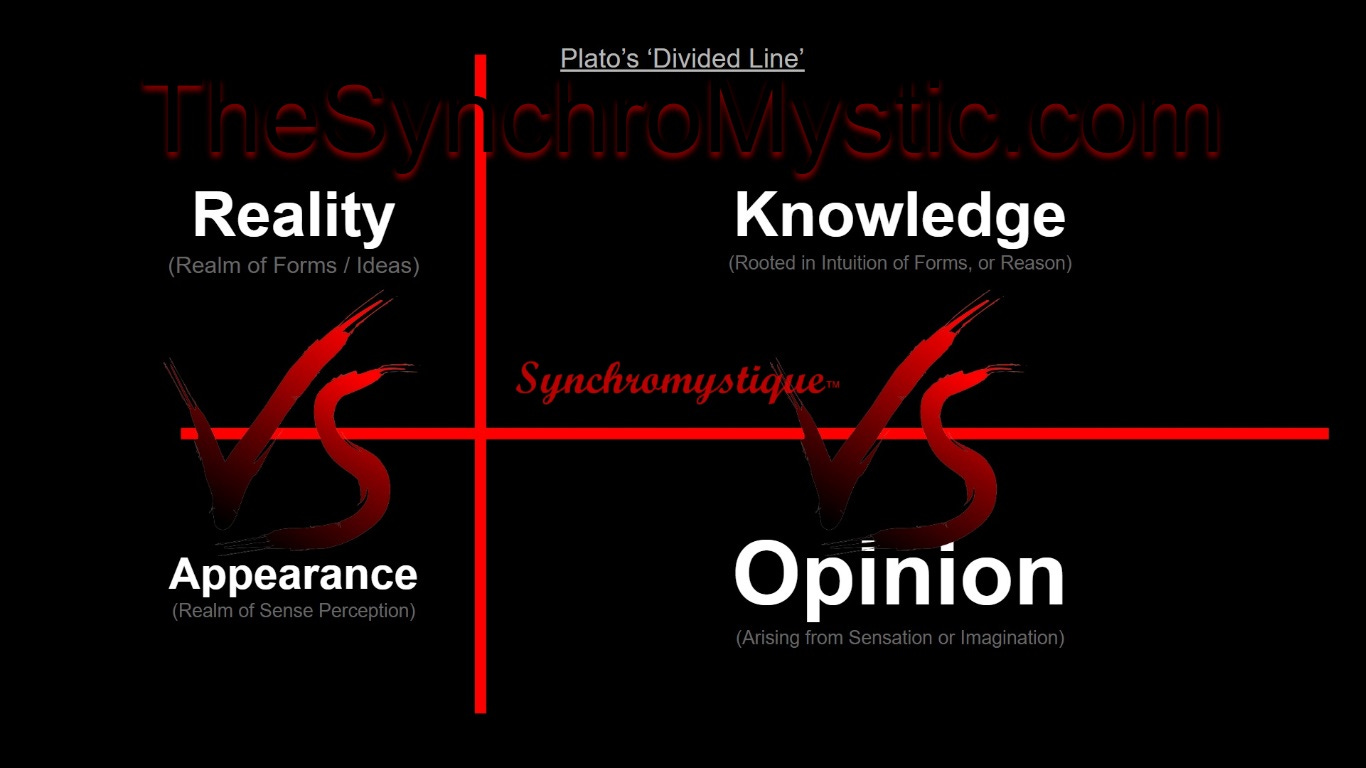

Shifting gears to epistemology, for Plato, sense experience cannot deliver knowledge. It’s only ever able to generate opinion. Plato represented this in his famous diagram of the “Divided Line.”

According to it, sense perception aims at the world of ever-changing, spatiotemporal particulars. As such, the deliverances of the senses cannot provide us with eternal, unchanging truths.

This was, of course, where — and why — Plato brought in his Forms. As spaceless, timeless, and everlasting, they provided the permanence and stability Plato believed was the sine qua non of knowledge.

Augustine recognized that Christian apologetics requires the reliability of sense experience and the possibility of (of at least some) perceptual knowledge. After all, Christians couldn’t trust eye-witnesses to Jesus’s post-Resurrection appearances if sensation only ever yielded opinions.

Augustine alleviated Plato’s concerns in several ways. One was to argue that God created our minds so that they could comprehend physical Creation. Explicating this lies far afield of our current project. But, for Augustine, the explanatory heavy lifting is again done by the doctrines of Divine Ideas (Forms) – this time as the rational patterns for all Creation – and Illumination.

Another maneuver, later taken up by Descartes, was to say that humans are made in such a way as to be able to trust the deliverances of our senses. The bulk of Descartes’s explanation lies in the reliability of God’s benevolence. Descartes thinks that we can know (in a robust sense) that God wouldn’t deceive us about our sensory experiences of the external world.

Finally, Augustine articulated a dualistic account of human understanding. Accordingly, we have a “lower” faculty of knowing (scientia), aimed at the physical world, and a “higher” capacity for wisdom (sapientia), actualized only when our minds are conformed to the Divine Ideas (Forms) and otherwise properly disposed to things of God.[122]

Conclusion

My purpose has been to sketch various ways that Augustine was arguably influenced, not only by Plato, such as Augustine’s affinity for Platonic notions of Forms and immortal souls, but also by Neoplatonism, as seen, for example, in Augustine’s accounts of evil, Illumination, and omnipresence.

Despite this, we reemphasize, Augustine nearly always managed to introduce his own unique — and Christian — “spin” on these doctrines. An obvious illustration of this was that instead of situating the Forms in some sui generis “Platonic Heaven” – as Plato had done – Augustine put them “in” the mind of God. Or rather than supposing that souls preëxisted embodiment and would be reincarnated after death, he respected the quite different account that he found in Biblical revelation.

Augustine’s innovations and strong personality led professors Armstrong and Blumenthal to say, in their previously cited article for the Encyclopedia Britannica, that “Augustine’s thought was not merely a subspecies of Christian Platonism but something unique — Augustinianism.”[123]

An analog of this classification issue arose in a previous video with respect to the important, “Analytic Philosopher” Bertrand Russell. The question was: Is Russell Platonic or anti-Platonic?

Without rehearsing the entire answer, the Cliffs-Notes version is: It depends! If you think that the “core” of being “Platonic” is adopting a mystical posture toward ultimate reality – as the Neo- platonists did from Plotinus onward – then (sure) Russell comes across as anti-Platonic.

Something similar could be said about Augustine. Listen to what one commentator, writing in the 1913 edition of the Catholic Encyclopedia, under the heading “Teaching of St. Augustine of Hippo,” said about the good bishop. “The rôle of Origen, who engrafted Neo-Platonism on the Christian schools of the East, was [akin to] that of Augustine in the West, with the difference, however, that the Bishop of Hippo was better able to detach the truths of Platonism from the dreams of Oriental imagination.”[124]

In other words, Origen and Augustine were both influenced by Platonism. The major difference was that St. Augustine downplayed, modified, or outright rejected the various magical, mystical, and miscellaneous religious intrusions introduced by Plato’s Neoplatonic successors; whereas, Origen – and, arguably, the entire ancient school at Alexandria – hewed much more closely to Pythagoras, Plato, Plotinus, and Plotinus’s successors (for good or ill).

Of course, Origenism – which included such doctrines as a “Subordinationist” Christology, a “Universalist” soteriology, an anthropology of preëxistence of the soul, and an extravagant preference for allegorical hermeneutics – was condemned multiple times, from local synods held at Alexandria (A.D. 399-400) and Constantinople (in 543) and, ultimately, at the “official” (ecumenical) Council of Constantinople II (553).

Such was not the outcome for Augustine, who was canonized a “saint” in 1303. “Nonetheless,” add the encyclopedists of the vaunted Britannica, “the reading of Plotinus and Porphyry (in Latin translations) had a decisive influence on …[Augustine’s] religious and intellectual development, and he was more deeply and directly affected by Neoplatonism than any of his Western contemporaries and successors.”[125]

When you think about these statements side by side, they imply that Augustine was basically able to “backwards engineer” or reconstruct an earlier form of Platonism from his interaction with Neoplatonic sources. Thus, although Augustine “conformed fairly closely to the general pattern of Christian Platonism,” his overall philosophy ended up being much closer to “Middle Platonic …than Neoplatonic [especially] in that[, for the saint,] God could not be the ‘One’ beyond Intellect and Being[,] but was [none other than] the supreme reality in whose creative mind were the Platonic forms, the eternal patterns or regulative principles of all creation.”[126]

Whether this was with divine guidance or not, it’s nothing short of astounding.

But, let’s leave aside the vexed topic of “mysticism.” After all, as we’ve said, to a large extent, mysticism was added by Plato’s disciples (such as Plotinus, Iamblichus, and so on) rather than by the old man himself.[127]

As already stated, if we take the most distinctively “Platonic” idea to be the existence of the aforementioned extramental, ideal “Forms” that undergird reality and give a philosophical “ground” to truth claims, then it turns out that both Augustine and Bertrand Russell were — in this sense — Platonists of some sort! (For Russell, at least at some points over his long career!)

That Augustine and Russell are worlds apart in numerous other respects (not least, their beliefs about God) shows that Platonism is a “big tent.” – which is what my taxonomy was hinting at.

But it shouldn’t surprise us that Plato’s influence was so wide as to affect both the Christian and Saint Augustine as well as the Agnostic-Atheist Bertrand Russell.

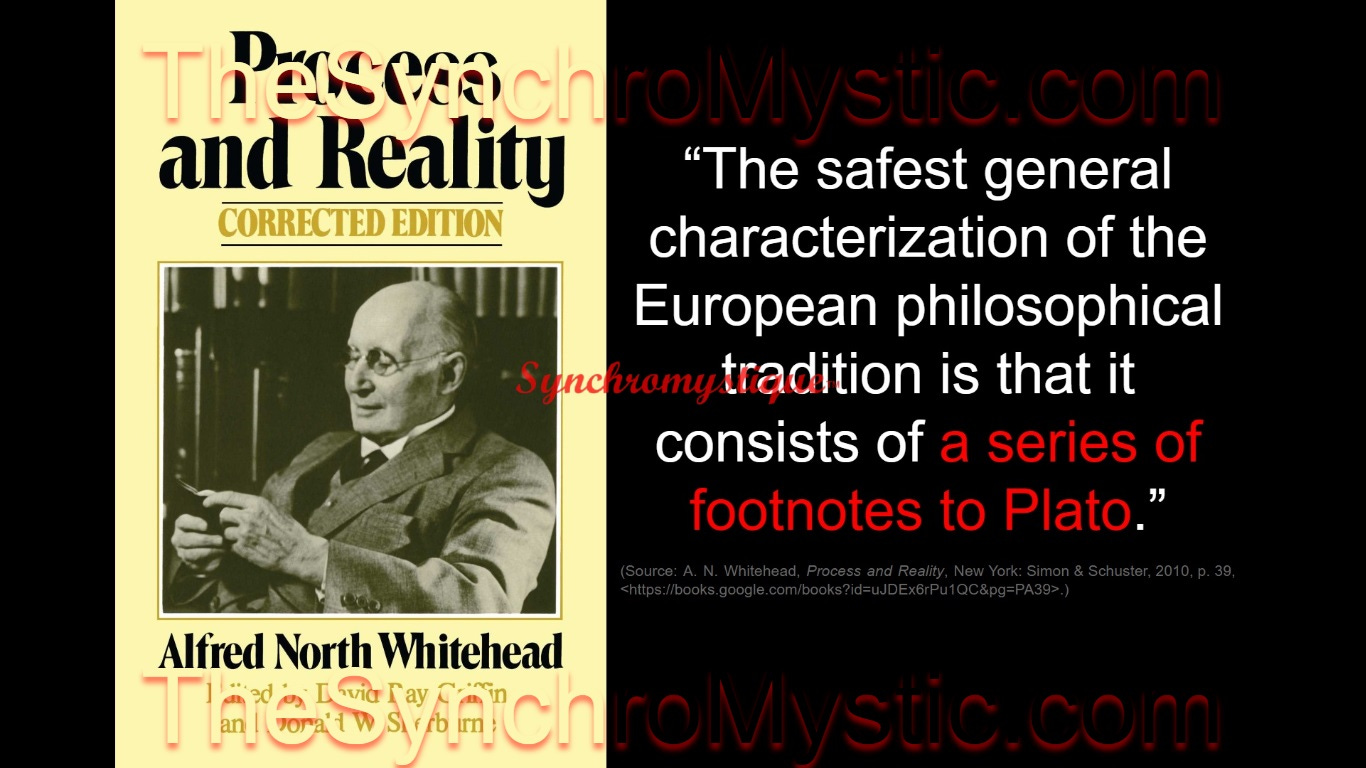

Recall Alfred North “A. N.” Whitehead’s quip that “[t]he safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists in a series of footnotes to Plato.”[128]

Socrates’s illustrious student was so influential that one is hard-pressed to find Western thinkers who have not been influenced – to one degree or another – by Plato.

At the same time, his degree of influence varies widely. And, to be sure, sometimes it’s a matter of disagreement rather than agreement. But, even in cases of opposition, one finds that Plato has, for all intents and purposes, often framed the discussion. This is the case as much with the Bishop of Hippo as with Russell – and with others, including Karl Popper who took the view that Plato’s Republic, often held aloft as a model of ideal society, was really nothing other than a blueprint for totalitarianism.

The thinkers impacted by Plato are so numerous, and cut across so many diverse fields (from art and literature, to education and psychology, to philosophy and theology), one could barely scratch the surface in an encyclopedia – let alone a single paper or video production. – or two!

Additionally, in-depth treatments could be written about each of the many persons who owe an intellectual debt to Plato – many of whom wrote voluminously and were influential in their own right.

We’ll just leave you with the thought that, if we had to pick a chief among those people who were – broadly speaking “Platonists” – Saint Augustine would be in the running, as it were.

Afterword: On Hermeticism

One academic, writing in 2021, states: “Some of the most interesting topics discussed currently regard the lines of continuity between the medieval and Renaissance receptions of Platonism and Hermetism [sic].”[129]

Since the bulk of this paper has focused on the former, it’s probably useful to say something about the latter as well.

“Hermeticism …was a long-standing school of philosophy drawn from the study of the Corpus Hermeticum, the magical texts attributed to the Egyptian priest, king, and philosopher Hermes Trismegistus, believed to …[have been] a contemporary and spiritual equal of Moses, which thus formed a source of wisdom on a par with the Old Testament…”.[130]

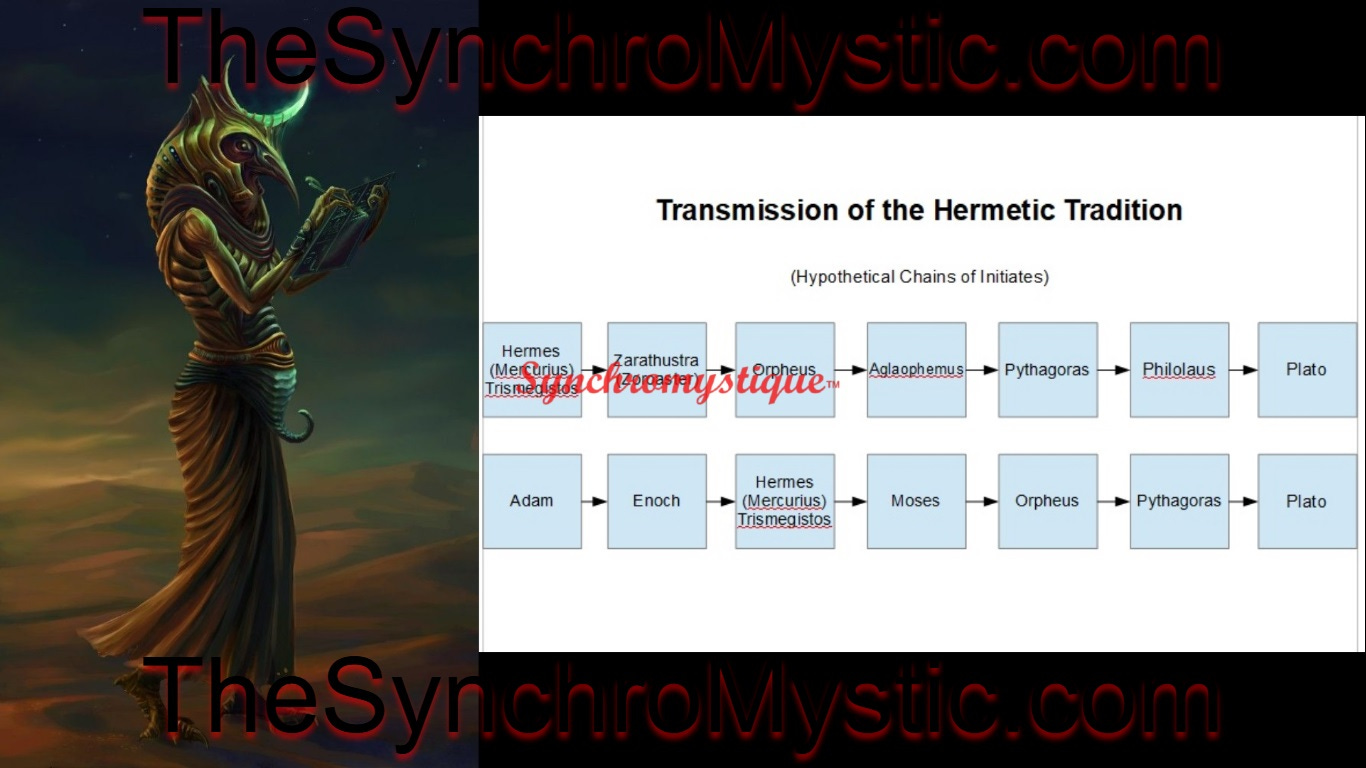

According to the 1993 book, The Egyptian Hermes, one of Hermeticism’s core historical contentions was that “[e]ven the wisest representations of other traditions – Moses among the Jews, Solon, Pythagoras and Plato among the Greeks – were acknowledged to have sat at the feet of Egyptian priests.”[131]

By the time you get to Iamblichus, it was a common scholarly opinion that both “Pythagoras and Plato ...visit[ed] ...Egypt” in order to study the Hermetica “with the help of native priests.”[132]

This manifested in (competing) lists of “sages” – that included such other far-flung characters as Orpheus and Zoroaster – who supposedly owed their learning to Thoth-Hermes.[133]

These beliefs tell us many valuable things about the thinkers who formulated and held them. But they tell us much less – if anything at all – about Moses, Plato, Pythagoras (et al.) themselves.

We’re confronted with a similar case in the so-called Apocryphal Gospels, (Gnostic) texts that make claims about the life of Jesus of Nazareth that are at odds with the picture given in the four canonical Gospels – Matthew, Mark, Luke, & John.[134]

“[T]he majority of these texts …[are] products of the 2nd and 3rd centuries, with little …relevance for answering questions about the historical Jesus of 1st-century Judaea.”[135] But the texts are highly intriguing for gaining insight into “the perspectives of their authors and of the communities that read them…”.[136] Thus…

From the fact that many Neoplatonists and others (from the third century A.D. on) thought that Plato had been a disciple of Hermes, or represented him that way, it by no means follows that he was a “Hermetecist” in any substantive sense – other than believing in the existence of souls or in the ability of the soul to (in some sense) “ascend” to the Divine.[137] After all, many Christian beliefs are close cousins in these regards, and yet Christians aren’t ipso facto Hermeticists.

Nevertheless, you may suspect it was inevitable that Hermeticists (from the 4th c. onward) would seek to interpret Christian luminaries – such as Saint Augustine – as one of their own.

Some “Hermeticists” did lay claim to Augustine. For instance, “…Giordano Bruno, Marsilio Ficino, [Tommaso] Campanella and Giovanni Pico della Mirandolla… used as sources… [t]hose Christian writers …(i.e., Tertullian, Lactantius, [Augustine], etc.) …who included Hemetism as part of [their defense of] Christian doctrines through quotations…”.[138]

A low-grade, contemporary example of this comes from the occult-friendly writer Jason Louv, who reports that “[e]ven previous Christian intellectual giants like St. Thomas Aquinas and St. Augustine considered Hermes Trismegistus a pagan prophet and forerunner of Christianity.”[139]

However, pace Louv, whereas the pertinent ancient Christians selectively quoted the Hermetica for apologetical purposes, that is, to buttress what is now called “orthodoxy,” the latter thinkers, by “classify[ing Hermes] as a wise pagan prophet who foresaw the coming of Christianity”[140] sought to lionize Trismegistus in furtherance of Renaissance syncretism. These goals differ.[141]

Or, consider Ananda Kentish “A. K.” Coomaraswamy. Coomaraswamy was a proponent of what is now called “Perennialism,” a philosophy (also espoused by René Guénon, Aldous Huxley, Frithjof Schuon, and others[142]) that tends to ground theological claims in religious experience and that holds that there is a “core” of truth detectable in (almost) all religions.[143]

Coomaraswamy’s premises led him (preposterously, in my opinion) to conclude such things as that Augustine’s maxim credo ut intelligam (“I believe that I may understand”) is a version of the Hermetic precept “as above, so below.”[144] (For a similarly doubtful assertion, pertaining to St. Thomas, see “Appendix B: Was Aquinas an Alchemist?”)

Christian Appraisal of Hermeticism

But that Augustine (inter alia) read from, interacted with, and selectively quoted the Corpus Hermeticum no more proves that Augustine was a covert Hermeticist than do the facts that William Lane Craig reads from, interacts with, and selectively quotes his atheist debating opponents reveal Craig to be a crypto-atheist. We need to know the verdict(s) they passed.

And it’s worth considering the history. Tertullian, the 2nd-3rd-c. Carthaginian Christian apologist and heresiologist, was consistently negative in his assessment of the Hermetica. “In his tractate against Gnostics (early 3rd c. A.D), Tertullian called ‘Mercurius Trismegistus’ …the father of all …occultism.”[145] “For Tertullian, Plato [himself] was ‘omnium hæreticorum condimentarius’ [‘the spice of all heretics’].[146]

“In the fourth century Hermes too was inculpated [accused]. Marcellus of Ancyra (d. c. 374), …held that all heresies were inspired by the impious trio of Hermes, Plato and Aristotle, since it was impossible that they could be founded on the pure and undivided traditions of the apostolic Church.”[147]

Or, again, “…Arnobius of Sicca, a pagan rhetor turned Christian polemicist…, writing in the early years of the fourth century, addressed his pagan opponents as ‘you who follow after Mercury, Plato and Pythagoras…’.”[148]

Simultaneously, you had the influential 3rd-4th-c. Christian apologist and Roman statesman “…Lactantius maintain[ing] a positive view of Hermes… [as] an authoritative Egyptian sage and theologian who preached Christian theology before Christ. …[Hermetic religion] …was a true, divinely revealed philosophy whose ultimate goal was piety toward God. In terms of its basic structure, this was exactly how Lactantius wished to present Christian thought.”[149]

Between these two extremes, Augustine seems to have steered something of a middle course. For St. Augustine, although “some aspects of the Hermetic doctrine were not the work of the Holy Spirit, but of a spirit of lies”, he nevertheless said that: “Hermes makes many …statements agreeable to the truth concerning the one true God who fashioned this world.”[150]

Augustine’s mediating position wasn’t unprecedented. It compares to that of Cyril of Alexandria, who favorably juxtaposed Hermes and Moses – saying the two were generally of “like mind” – with the caveat that “…[Hermes] was not correct and above reproach in everything.”[151]

Still, Augustine clearly “condemned all kinds of magic and classified incantations, charms, necromancy (goetia) and theurgy as demonolatry. He addressed …[several] chapters [in The City of God] against Platonists like Porphyry who insisted on the divine aspects of theurgy.”[152]

Notice that the “red line” for Augustine was anything having to do with sorcery.

“…Augustine of Hippo’s De Civitate Dei (‘City of God’) …taught that pagan gods were demons and that magicians drew upon satanic power whether they realized it or not.”[153]

Hermeticism’s Different ‘Flavors’

Just as Plato’s philosophy ramified – into Middle Platonism and Gnosticism,[154] Neoplatonism (of various sorts, according to me), and Augustinianism – so too was there variation within “Hermeticism.” There are a couple of illustrations of this variety

Take the honorific “Trismegistus” itself, which translates into the phrase “Thrice Great.” For some enthusiasts, Hermes’s triple “greatness” owed to his alleged mastery of alchemy, astrology, and magic.

According to other believers, the title was a take-off of Jesus Christ’s special prerogatives in the Lord’s capacity as prophet, priest, and king – following Moses, Abel, and David, respectively. Quite likely, the two explanations dovetailed in hermetic imaginings.

A second example of Hermeticism’s diversity applies to the story of Hermes’s origins. As mentioned above, Hermes the Three-Times Great emerged from Egyptian myth, where he supposedly started off as the god variously known as Tahuti, Theuth, Thoth, etc.

By the fourth century, A.D., some Greek Hermeticists took “the line of least resistance” and continued to “[depict] Hermes in [these] …unmistakably Egyptian terms…[,] propagat[ing] a version of Trismegistus that was scarcely Hellenized at all except in name.”[155]

On the other hand, there were Hermeticists “who looked at things from a [more thoroughgoing] Greek point of view, [and] …to some extent played down [various] specific Egyptian elements and assumed that, in origin at least, Hermes had [initially] been human.”[156]

Incidentally, during the late 2nd century A.D, Clement of Alexandria accused pagan Greeks – who went the Hermes-as-human route – of atheism. “In his ‘Exhortation to the Greeks’ …[,] He claimed that the pagan gods were nothing but divinised ancient men – thus, fake gods.”[157] But…

If Christian polemicists asserted Hermes’s humanity as an attack on Hermeticism, it invites the further question, what did the Hermeticists themselves believe about Trismegistus’s origins?

Was Plato a Hermeticist?

Plato becomes relevant here because – without coming down clearly on one side or another – he puts into the mouth of Socrates an allusion to “an Egyptian story that… [a] god or godlike man… [whose] name was Theuth…”.[158]

In another place, Plato has Socrates say that Thamus, the mythical Pharaoh of ancient Upper Egypt, was taught the art of writing from Theuth (Thoth). Thamus minimizes his use of it on the supposition that over-reliance on writing – which, in Socratic fashion, we might call “artificial memory” – may destroy one’s natural memory.[159]

Mostly, these references to Hermes are nothing more than one-liners. It’s for this reason that Plato is not usually classified as a “Hermeticist” himself. I’m unaware of any dedicated Plato scholar who represents him that way.

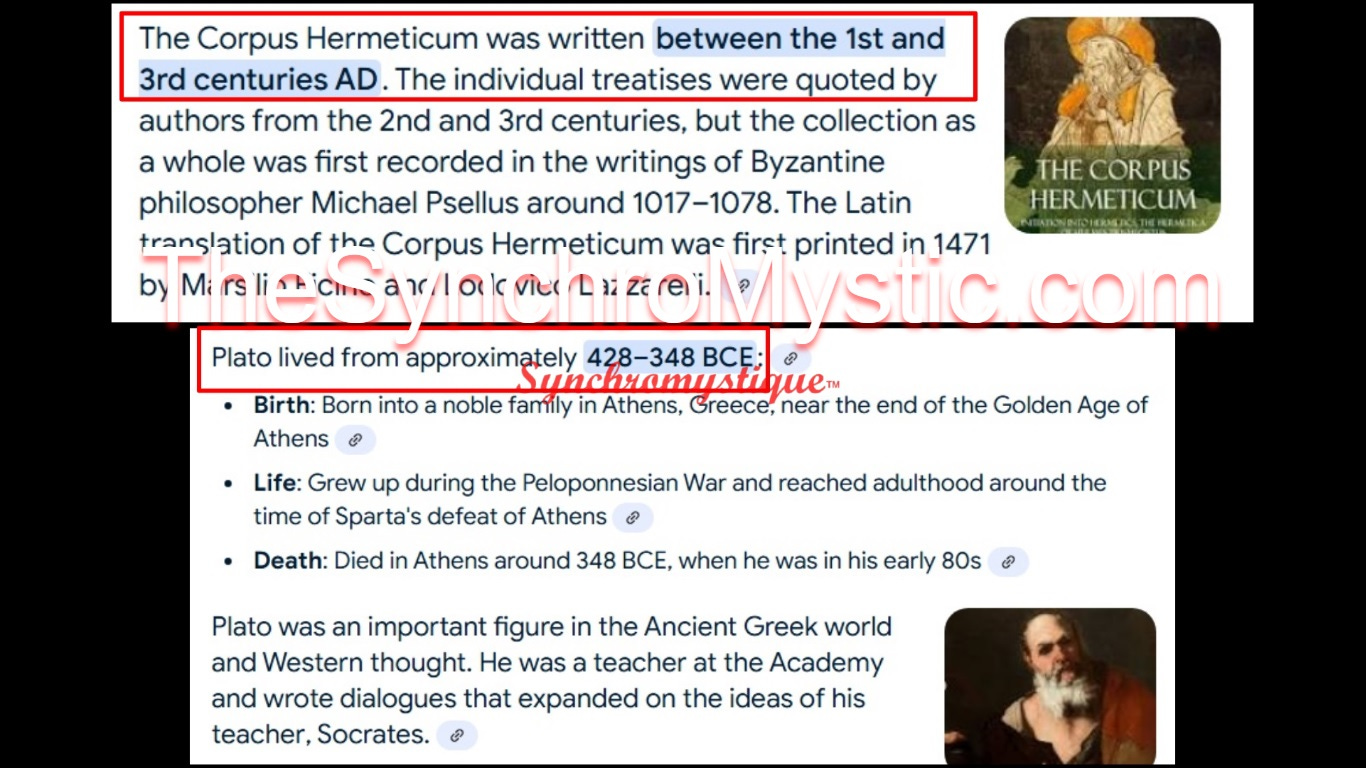

Indeed, the possibility that Plato was a Hermeticist (in the most obvious sense, namely, that he pored over the Hermetica) can, for all intents and purposes, be laid to rest by the philological thesis of 16th-17th-c. French-Swiss scholar Isaac Casaubon.[160] According to Casaubon,[161] the Corpus Hermeticum, which was more or less the definitive articulation of the Hermetic worldview, was written between circa A.D. 100 and 300, rather than in some primordial period.