Neoplatonism

A Historical and Philosophical Overview

Neoplatonism is a philosophy, emerging in the Greco-Roman world around the third century of the common era, that built on – and modified – various ideas that were first articulated by the towering, 4th -5th -c. B.C.-Athenian thinker, Plato.

20th -c. British philosopher Anthony Quinton once characterized Neoplatonism as a “mystical re-reading” of Plato’s ideas.[1] This helpfully conveys the fact that Neoplatonism has one foot in the door of philosophy and rationalism, and the other in mysticism …and even magic.[2]

In the words of William Lawhead: Neoplatonism is a “religious Platonism”.[3]

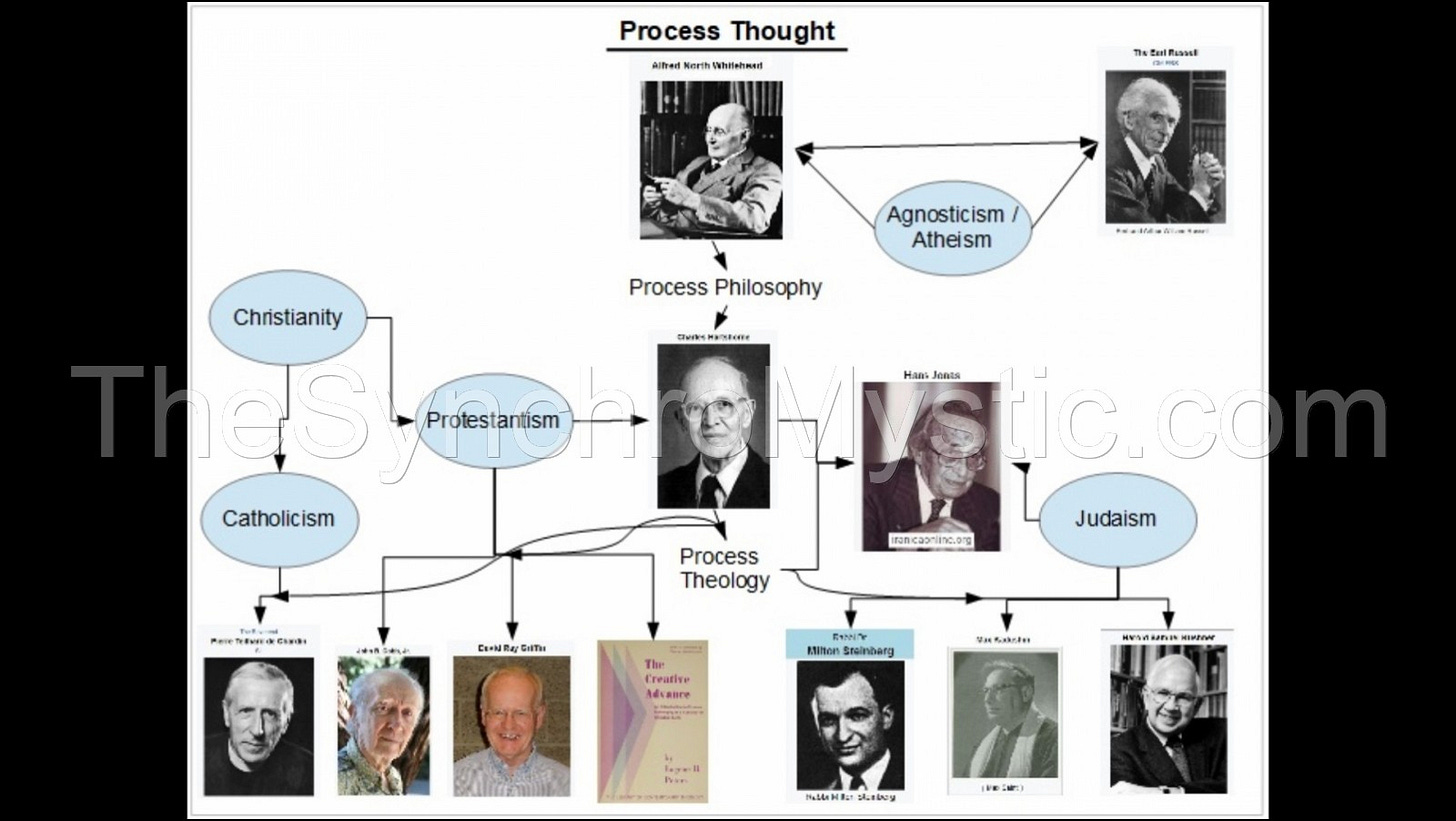

It’s worth stating at the outset that Plato has had many followers of varying hues. In fact, British philosopher Alfred North Whitehead, whose own “Process Philosophy” has been identified as a contemporary reworking of Plato’s ideas,[4] once remarked: “The safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato.”[5]

Because of this almost incalculable impact, “Platonic” ideas are liable to show up in a host of contexts. It is sometimes difficult to disentangle mystical “Neoplatonism” from other forms of “Platonism” more broadly construed. Not only this, but various authors use one word or the other – “Platonism” and “Neoplatonism” – to refer to either kind of philosophical tradition. In those cases, only a fuller examination of the details being considered will reveal which sort is under review.

So... what are some of the distinguishing features of Neoplatonism – in the mystical sense? And who were some of the people associated with it? We’ll look at both of these questions, in order.

Note: There is a video-version of this presentation available on YouTube, HERE.

What Is Neplatonism All About?

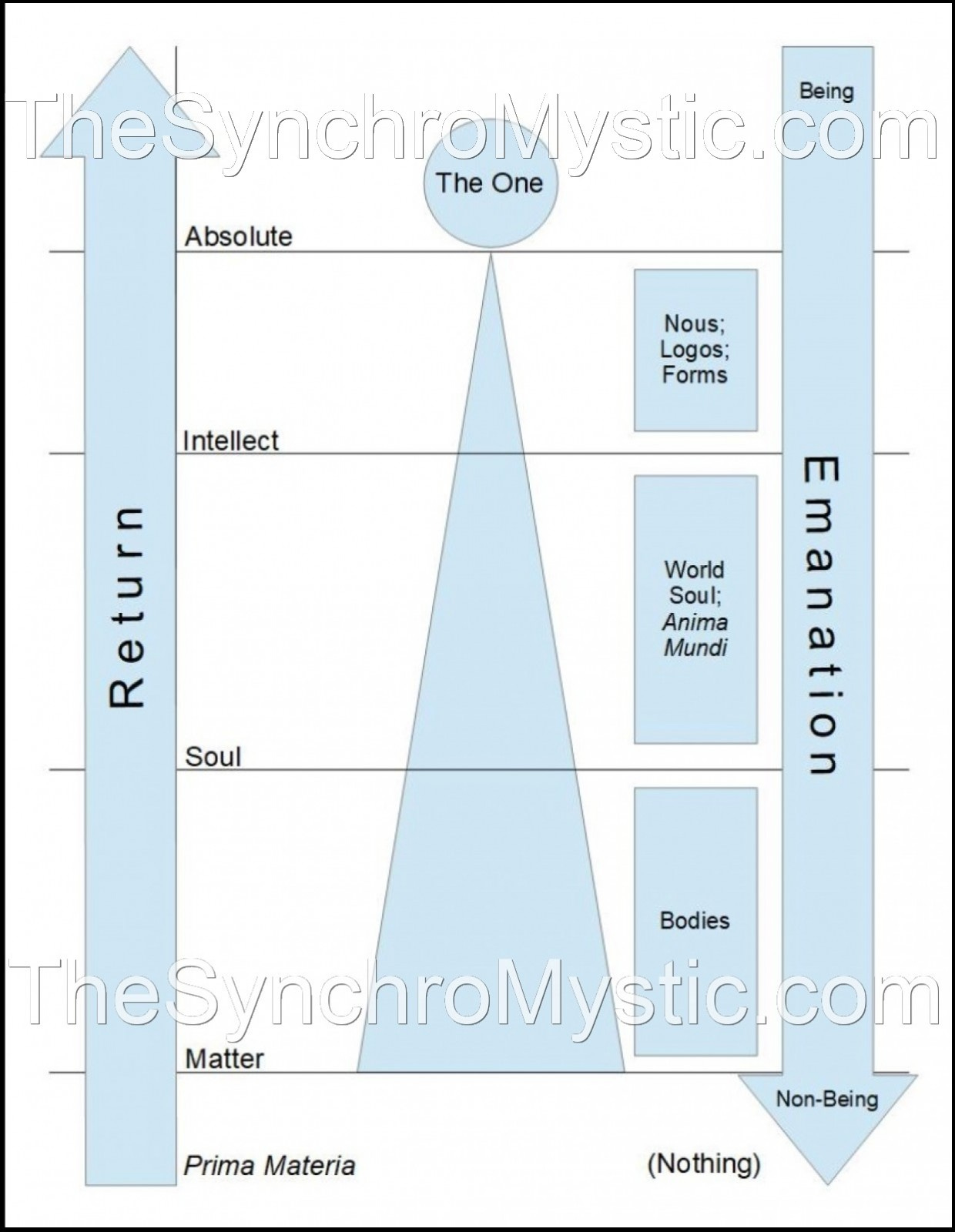

I suggest that there are five characteristics you should focus on to get a sense of what makes up the core of Neoplatonism. These are: (1) Neoplatonism’s ontology, namely it’s view that the world consists of a hierarchy of entities with “something” called the “One” at the very top. (2) Neoplatonism’s doctrine of emanation – that all lower realities emerge or trickle out of the One. (3) Neoplatonism’s pantheism – it’s virtual identification of the divine with the entire universe. (4) Neoplatonism’s related mysticism – or its conviction that human souls will not experience goodness or truth unless and until they “reunite” with the One. And (5) Neoplatonism’s tendency towards syncretism; that is, its attempt to combine the religious and philosophical ideas of various systems. Let’s go through each one in greater detail.

Neoplatonic Ontology: Hierarchy & The ‘One’

Central to the Neoplatonic outlook is the concept of a hierarchical cosmos composed of various “levels” or “spheres of reality.” This has been called the “Great Chain of Being.”

At the top of this complicated schema lies the mysterious “One.”

The idea of the “One” comes directly from Plato’s dialog titled the Parmenides.[6] It has become standard to associate it with Plato’s Form of the Good, which is extensively described in what is perhaps his most famous writing, the Republic.[7]

Put in simplest terms, Plato’s theory of “Forms” basically held that the everyday, physical world of our experience is merely the ever-changing and imperfect shadow of a perfect and unchanging realm of timeless Ideas called the “Forms.”

Forms are the truest manifestation of reality. What we bump into in the physical world are mere approximations, echoes, and shadows of the Forms. At the same time, particular objects – like dogs and trees and people – are the kinds of things that they are in virtue of their “exemplification of” or “participation in” one (or more) Forms.

Fido are Rover are both dogs because they both participate in a Form we may call “Dog-ness.”

The crab-apple tree in my front yard and the dogwood in my back yard, despite their differences, are both trees because they exemplify the Form of Tree-ness. You and I both share Human-ness. And so on.

A lot of problems and questions arise for proponents of this view. For example, are there subsidiary Forms for Crab Apples and Dogwoods? Are there Forms for unsavory objects such as excrement? Do the Forms participate in themselves? These – and many others – are taken up by subsequent thinkers, including Plato’s chief student, Aristotle. Indeed, Plato tackled many of these questions himself.

We will ignore all this and simply observe that, however many Forms exist (if any exist at all), Plato seems to have ranked one above the rest. This is his Form of the Good – symbolized by the sun.

To the nearest approximation, then, these two Platonic Ideas of Oneness and Goodness are brought together to yield the skeleton of the Neoplatonic “One.”

If you add to this a species of reverence for the One, an attitude ostensibly imported from “Oriental” religion,[8] then you have fleshed out some basic doctrines of textbook Neoplatonism.

For the orthodox Neoplatonist, humans are incapable of saying much of anything meaningful about the One. It is essentially undefinable. This is because to “define” something is to distinguish it from everything else – to indicate what a thing is by separating it from what it is not. For example…

Triangles as closed, three-sided, geometrical figures. In defining triangles this way, we’re simultaneously saying that triangles are not squares. They’re not circles. They’re not straight lines.

But the One is or permeates or underlies all reality. Somehow the One contains all and is all. Therefore, there is nothing from which it can be separated. If a thing is definable, then, it isn’t the One.

Neoplatonic Cosmogony: Emanation

This caveat notwithstanding, Neoplatonists nevertheless held that One – this ineffable, unknowable Absolute – is at once the source of all being and the end (or telos) of human existence.

The One is the “source” of reality because, somehow “out of” the One, by an equally mystifying process termed “emanation,” flow the lower levels of being previously mentioned.

These realms “flow from” the One something like light radiates from the sun. They are commonly given a threefold description, as follows.

Firstly, we have the realm of Intelligence. This is often referred to as the province of something called nous, or “mind.” The concept goes back to the presocratic thinker Anaxagoras, who thought of nous as the organizing principle of the cosmos.

Other times, this level of Intellect is referred to as the logos, which basically means “reason.” This term was imported from the enigmatic philosopher Heraclitus. It was funneled through Greek Stoicism, where – similar to Anaxagoras’s nous – it signified the orderly regulator of all reality.

Eventually, it informs Trinitarian Christianity, by way of Middle and Neoplatonism, where it becomes associated with the “second person of the Godhead,” Jesus Christ – especially in his preëxistent form.

But, in Neoplatonism, its primary characteristic is its rationality. Because we can say this, we may also say that it is the first emanation of the One that is definable.

Secondly, there is the realm of Soul. In Greek, the word is psuchē, which is more frequently transliterated with the letter “y” and pronounced “psyche.” This realm is dominated by an entity known as the “world soul.” In Hermeticism and later systems, the world-soul concept is sometimes designated by Latin phrases such as anima mundi and spiritus mundi.

(For a sketch of Hermeticism, with particular emphasis on differentiating it from allied doctrines, such as those of Gnosticism and Neoplatonism, see “10 Arcane Words That Are Frequently Confused.”)

Thirdly, we have the familiar – and lowly – physical world of matter, or hylē. This is the commonplace realm of day-to-day activity for most of us.

We don’t need to get bogged down on the particulars. The important things to note are, number one, the closer something is to the One, the better and more unified it is, and the further away something is, the more divided and worse it is. And, number two, the being or existence of each of these lower spheres – however deficient they may appear – is ultimately owed to, and derived from, the One.

Neoplatonic Theology (I)

Pantheism

Because Neoplatonists tend to view the One religiously, as something akin to the way a more traditional theist would view God, the entire system is sometimes characterized as – or at least compared to – an idea known as “pantheism.”

The Greek word pan means “all,” and the root of “theism” – theos – means “god.”

To put it in contemporary language, “pantheism” carries the sense that everything – for example, the entire universe considered altogether – literally is the same thing as God. Everything is god.

Though, for the Neoplatonist, this has to be qualified somewhat since the process of emanation introduces degradation or undesired plurality into the inexpressible simplicity of the One.

Additionally, as previously stated, since the One is held to be indefinable, Neoplatonic theology – its doctrines about the divine – tends to be “negative.” Thinkers adopting this “negative way” (or via negativa) will speak only of what the One is not. The One is not limited. The One is immortal, indefinable, unknowable, and so on.

This approach – also called “apophatic theology” – has carried over into Christianity, especially in the major branch known as Eastern Orthodoxy.

Neoplatonic Theology (II)

Mysticism

But a moment ago, we also said that the One is the end[9] (or goal) of human existence. And now we’re in a better position to see why that is.

For while our embodied human souls are languishing in the lowly world of apparent multiplicity, we will never truly experience the highest truth: namely, the unified Good – the One itself.

This indisputably Platonic “note” sounded by Neoplatonism is merged with a Neopythagorean emanationist scheme. (For more on Pythagoras, see the dedicated video, HERE).

Emanation flows two ways – so to speak. Not only do the various spheres of reality proceed out of the One, but everything – including human souls – can, in principle, ascend the chain of being and “return to” the One.[10]

It is for this reason that Neoplatonism often appeals to people who have mystical inclinations – that is, people who seek a way of having a close experience with, or even of merging into, the divine.

As such, this spiritualized philosophy thrived among some of the ancient adherents of “Mystery Schools” like those relating to Dionysus and Orpheus, as well as the so-called “Eleusinian Mysteries” and, later, Mithraism.

Neoplatonic Theology (III)

Syncretism

Mention of these various, ancient-Greek religious systems leads us to the last point we’ll consider, here. Neoplatonism has a marked tendency towards syncretism.

The prefix “syn-” means “to bring together,” or “to combine.”

For example, to “synchronize” watches requires setting them all at the same time. You’re bringing all the watches together.

Similarly, “syntax” refers to a language’s rules about how to properly arrange words to form intelligible expressions. Syntax dictates how to combine words.

In this case, to be syncretistic in your thinking is to draw together diverse – and, possibly, seeming unrelated or even contradictory – ideas into a single, unified system.

In its Hellenistic historical context, Neoplatonism is something like a tapestry composed of pieces gleaned from philosophies that came before it.

University of Pittsburgh Classics professor Christian Wildberg writes that the Neoplatonists achieved a “Grand Synthesis” of the varied traditions they had inherited: “In effect, they absorbed, appropriated, and creatively harmonized almost the entire Hellenic tradition of philosophy, religion, and even literature…”.[11]

The decisive influence of Plato has already been highlighted. But the Neoplatonists even incorporated much from Plato’s student Aristotle, who is often – and not without reason – understood as becoming his teacher’s intellectual rival. In fact, Aristotle’s impact is evident in the Neoplatonist concept of the Intellect[12] as well as in Neoplatonism’s adoption of Aristotelian logic.[13]

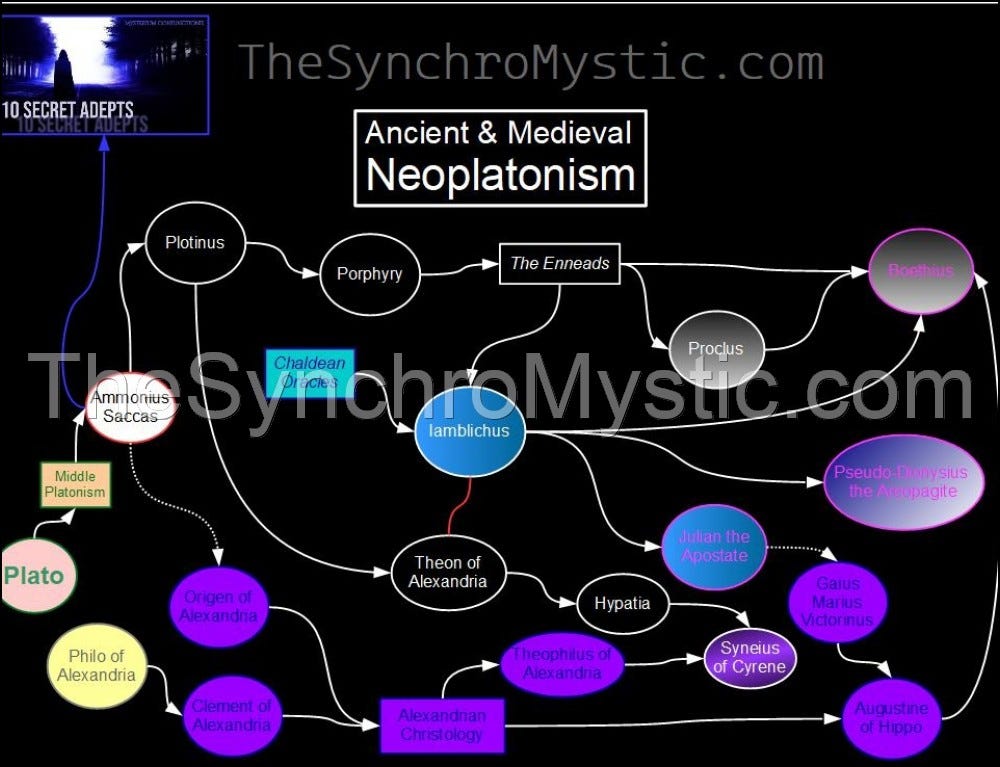

As hinted at earlier, the concept of emanation can be traced back to Pythagoras via two seldom-mentioned precursor movements usually referred to as Neopythagoreanism, of whom the reputed Hermetic sorcerer Apollonius of Tyana (ca. 3 B.C.-A.D. 97) was a notable example, and Middle Platonism, represented by the philosopher-historian Plutarch (A.D. 46-120). The fusing of these two streams in the thought of Numenius of Apamea (fl. 2nd c. A.D.) prefigured Neoplatonism.

Who Were the Neoplatonists?

Ancient Neoplatonists

The philosopher Plotinus (204-270 A.D.) is usually credited with being the originator of Neoplatonism. However, among those people who put Plotinus on his path was the shadowy Ammonius Saccas (175-242), about whom little is known.

According to one persistent story, Ammonius Saccas was a sage from India. If true, this would suggest that Neoplatonism could have been a “Græcized” form of Hinduism. For more, look for our video “10 Secret Adepts” or “Mystery Men.”

Be that as it may, Plotinus’s lasting influence was guaranteed by his student Porphyry (234-305) who transmitted his teacher’s Neoplatonism in a book called the Enneads (“Nines”), which he edited. If Neoplatonism was founded by Plotinus, it was first codified by Porphyry.[14]

The subsequent communication of Neoplatonism is somewhat complex. For a bird’s-eye view, look for various charts – some of which I will post on TheSynchroMystic.com, and others of which I will try to soon offer for sale on Amazon.com.

However, the two “post-Plotinian” figures usually singled out for special mention are Iamblichus (245-325) and Proclus (412-485).

Iamblichus is highly noteworthy because of his introduction of magic into the already mystically suffused philosophy of Neoplatonism. The Greek word is theurgy – which means, literally, “work of God,” but which has the sense of “sorcery.”[15]

One of the chief inspirations and sources of Iamblichus’s magical Neoplatonism was an important ancient text known as the Chaldean Oracles.

In the mid-4th c., Theon of Alexandria (335-405) attempted to revive the non-magical, original Neoplatonism of Plotinus. Scholar Edward Watts relates that “Theon [of Alexandria] may have kept Iamblichan influence out of his curriculum with a certain amount of pride.”[16]

Theon’s apparently short-lived school of mathematics and philosophy produced one of the most famous female intellectuals of the age, his ill-fated daughter, Hypatia (360-415) who was said to have been murdered by a mob. The reasons for this barbarous act are disputed.

This “reform” movement notwithstanding, Iamblichus’s magical Neoplatonism has seemed to have been a dominant stream ever since its inception, arguably reaching its fullest expression in Proclus.

Shortly after his tenure leading the philosophical school in Athens, Neoplatonism officially fell out of favor – especially with emperors such as Justinian I (482-565), who had embraced Christianity. At this point, the era of “ancient Neoplatonism” basically closes.

But the story of Neoplatonism is far from over.

Medieval Neoplatonists

Neoplatonism lived on, via offshoots. In fact, it can be helpfully thought of as launching along three or four distinct trajectories.

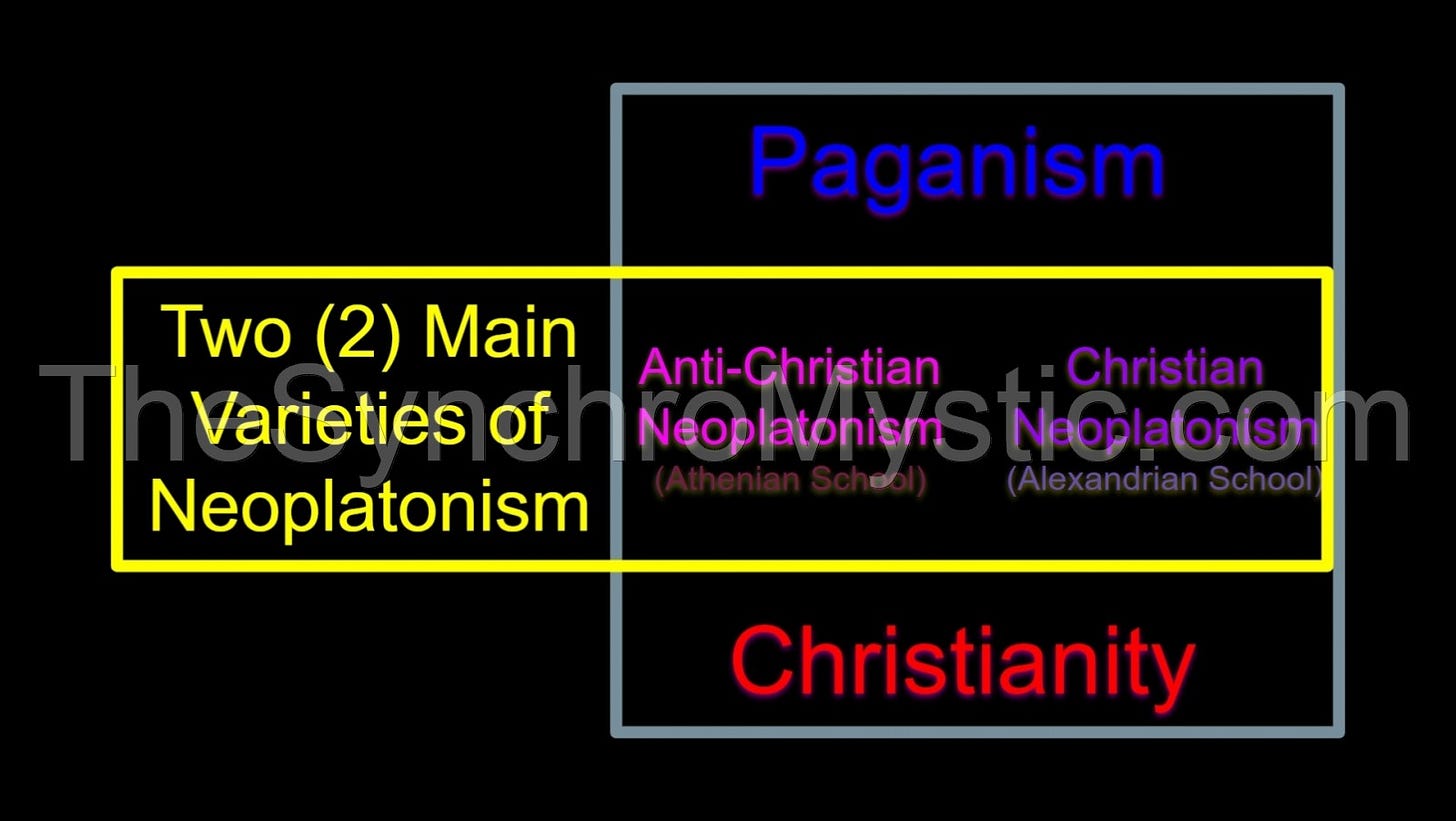

Pagan Neoplatonism

One group picked up where Iamblichus left off. This variety of was explicitly pagan. This is to be expected, since “…Porphyry and other [early] Neoplatonists were decidedly anti-Christian.”[17]

These thinkers amplify Platonic themes such as “…reincarnation, a doctrine incompatible with the biblical account of the afterlife.”[18]

For the Neoplatonist, human fulfillment lies in the exercise of “autonomous reason,” and culminates in a mystical return to the One, rather than in cultivating a relationship with a personal Creator-God.[19]

Or again, as we have seen with Neoplatonism, the One,[20] is often construed as a form of pantheism.[21] Since all reality is a series of emanations from the One, the Neoplatonist comes close to saying that everything is “made of” bits of the One – albeit in a degraded and rarefied way.

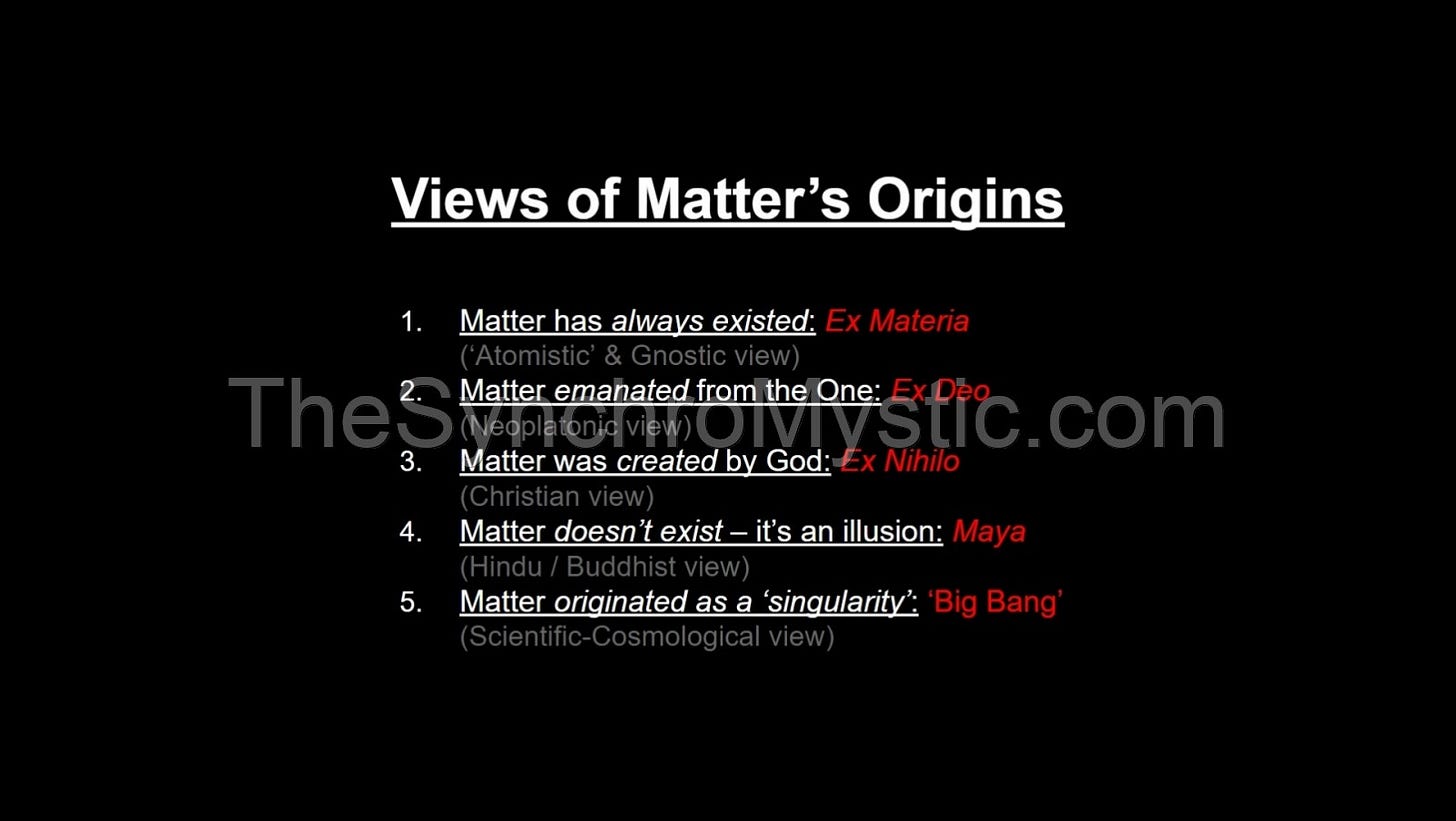

On this view, matter proceeds ex Deo; that is – quite literally – out of God’s being (i.e., out of the One). This process is, presumably, inevitable and necessary. It is somehow the nature of the One to emanate.

By contrast, in Christianity there is an ontological separation between God (on the one hand) and everything else (on the other). Sometimes this is referred to as the “Creator-creation distinction.”

This goes back to the ancient Hebrews, for whom the opening lines of the Book of Genesis – “In the beginning, God created the heaven and earth” – came to mean matter was fashioned by God ex Nihilo[22] – that is, literally “out of nothing.”[23]

The most obvious representative of this later Pagan Neoplatonism was the 4th-century Roman emperor who was labeled “Julian the Apostate” by his Christian opposition.

Some fundamentals of Christianity had been articulated at a gathering of church leaders held in Asia Minor, in the city of Nicæa in 325 A.D. After this version of Christianity gained traction under Constantine the Great, Emperor Julian led an opposition movement that attempted to resuscitate – and reinstate – Latin paganism.[24] “With Julian the dynasty of Constantine came to an end.”[25]

Julian’s version of Neoplatonism leaned heavily on the magic-infused variety of Iamblichus.[26]

Christian Neoplatonism

A second main variety of Neoplatonism was relevantly different. This Neoplatonism was Christian – to one degree or other. This may seem strange for a couple of reasons, not least of which the previously mentioned antipathy of early Neoplatonists towards Christianity.[27]

For all the animosity (which was often a two-way street), some Church Fathers had a fondness for Plato himself. For example, the apologist Justin Martyr (circa A.D. 100-165) referred to Plato – and Plato’s teacher, Socrates, as “Christians before Christ.”[28] Furthermore, during the early Medieval period,[29] …

Plato’s works were largely unknown. The Timæus[30] was an exception. It was “concern[ed with] the creation of the world by a Demiurge,” a lesser deity who formed the cosmos out of chaos using preexisting materials. The Demiurge loomed large in Gnosticism, on which, see past videos.

Despite all this, we may discern two main “flavors” or subtypes of Christian Neoplatonism.

Catholic Neoplatonism (Augustinianism)

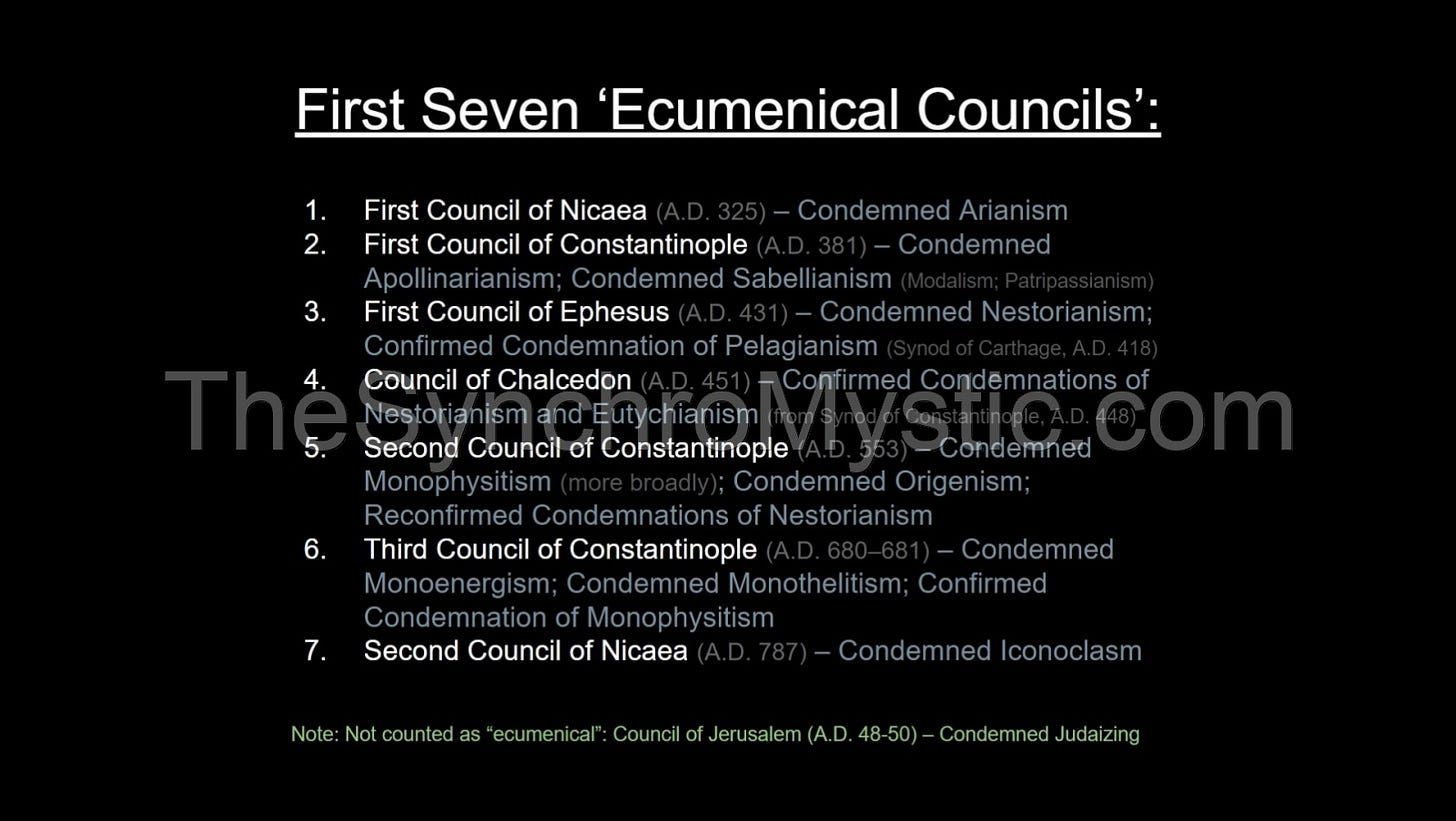

One sort is that which developed in tandem with the growing Catholic orthodoxy – at least, as its dogma was successively codified at meetings – called “ecumenical councils” – that followed the initial, successful Council of Nicæa.

Some of the most important of these seminal gatherings included the Council of Constantinople (in A.D. 381), the Council of Ephesus (431), and, ultimately, the decisive Council of Chalcedon (451).

The initial stirrings of Catholic Neoplatonism go back to a group of scholars in Alexandria, Egypt.[31] Known as the “Alexandrian School” of theology, it – with its penchant for an allegorical interpretation of Scripture – influenced such Church Fathers as Clement[32] (ca. 150-215), Athanasius[33] (ca. 296-373), and Cyril[34] (ca. 376-444) – all of whom are today recognized as “saints” in the Catholic Church.

This Alexandrian-Christian Neoplatonism was transplanted to the “East,” where it is evident in the theology of people such as Sts. Basil (330-379), Gregory of Nyssa (335-395), and Gregory of Nazianzus (329-389) – which three are, collectively, known as the “Cappodocian Fathers.”

Without question, though, the most significant figure of the age to have been influenced by this stream of Neoplatonism was St. Augustine of Hippo[35] (AD 354-430). One of the towering “Doctors” of the Western Church, Augustine looms so large during the Middle Ages that, in many conservative-leaning contexts, “Christian Neoplatonism” is a virtual synonym for “Augustinianism.”

Although he had been born in a Christian-believing home, Augustine abandoned this faith for almost a decade, and lived a sexually promiscuous lifestyle. Additionally, he joined the Manichæans – a group that owed its existence to the 3rd-century Persian prophet Mani, as we mentioned in “Top 10 ‘Sex-Magic’ Cults.”[36]

However, in Milan, Italy, Augustine was introduced to a Catholic Bishop – and later Saint – named Ambrose. St. Ambrose exercised an enormous impact on his thinking.

There are several relevant biographical factors. I will simply mention it was at that time that Augustine became acquainted with the thought of the chief Neoplatonists, Plotinus and Porphyry.[37]

It could be said that Augustine crossed over a Neoplatonic bridge into Christianity from Manichæism.

Indeed, a Neoplatonic influence is evident in several of Augustine’s doctrines. Number one, it arguably informed Augustine’s belief that evil was a “privation.”

In Gnostic Manichæism, evil is a force opposed to the equal and opposite power of goodness. “This opposition of good and evil is called dualism,” as we noted in “Gnosticism Explained in 5 Minutes,” & it shows up in several religions including Zoroastrianism, from which Manichæism heavily borrowed.[38]

In contrast to this dualistic view, Augustine held that while good had “positive” being, evil was simply a lack of good. To illustrate this, think of light and darkness. When you turn on the switch, the room fills with light. But, when you turn the switch off, it’s not like something else – darkness – comes streaming into the room and pushes out the light. Rather, it’s simply that the light goes away. To say “the room is dark” is just to say it has no light. Similarly, on Augustine’s view, to say that something is evil is simply to say that whatever it is (whether an action, a person, etc.) is lacking good.

But this view is reminiscent of the Neoplatonic “hierarchy of being,” in which every existing thing is derived from, and owes its existence to, the One. On such a view, there is only one “principle of being,” so to speak. All existing things are differentiated from one another in terms of the varying degrees to which they lack being.[39] Towards the top of the chain are the Logos and the World Soul. Though not perfect, they enjoy a lot of being, since they are closest to the One.

Towards the bottom, we find the world of matter. This verges on outright non-being, because it is as far from the One as it is possible to get.

Number two, Neoplatonism is arguably apparent in Augustine’s epistemology – that is, his view of how humans acquire knowledge. According to Augustine’s doctrine of “Illumination,” we only achieve a state of knowing when (and if) God directly intervenes to enlighten our minds.

In this, Augustine was influenced by the Neoplatonic “notion that the eternal ideas or forms …subsist in the mind of God,”[40] or – in Plotinus’s vocabulary – the Logos. You’ll recall that, for Plato, the “Forms” are those invisible realities which make particular things what they are.

For Plato, these Forms just existed “out there” – in what is sometimes half-jokingly called “Platonic Heaven.” Remember, for Plato, humans undergo successive cycles of birth and death. In between, we exist in the spaceless, timeless realm of the eternal Forms. Our knowledge of Reality lying behind particular things arises when we “remember” these Forms.[41]

For Augustine, though, the Forms are not in any “Platonic Heaven.” They are “in” the mind of God.

And for Augustine, humans do not reincarnate. As it says in the New Testament Book of Hebrews: “[P]eople are destined to die once, and after that to face judgment…”.[42]

Therefore, to Augustine, our perception and knowledge of particular objects is dependent upon God. God shares “the eternal ideas or forms” with us “with the result that we acquire eternal and immutable truths about the objects.”[43] Without this divine illumination, knowledge would be impossible.

Moreover, unlike thoroughgoing Neoplatonists, Augustine is committed to taking the Bible seriously – both as God’s authoritative Word to humanity and as a reliable history of the life of Jesus of Nazareth. Given this, Augustine distances himself from textbook Plotinian Neoplatonism in important ways.

For instance, whereas Neoplatonists tended to be expositors of emanationism, pantheism and (as we said) reincarnation, Augustine was keen to stress the ontological separateness and creative activity of God as well as a linear (rather than a cyclic) view of cosmic and human history.

These changes make a difference for mysticism and religious practice. Pagan Neoplatonists approach “ascent to” the One as a means of realizing a strict identity with it. To put it another way, the Neoplatonic mystic thinks of herself as trying literally to unite with the One.[44] On the other hand…

Augustinian mystics, such as St. Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153),[45] describe the mystical experience in terms of achieving, even if only temporarily, harmonious conformity between a believer’s desire and will and God’s perfect will. It is, therefore, unity of purpose rather than a strict ontological “sameness.”

St. Anselm of Canterbury adopted an Augustinian outlook as well. And the influence of Augustinianism continued well into the Scholastic period. The learned monk William of Champeaux (1070-1121) was an Augustinian. William of Champeaux founded the School of St. Victor where orthodox mystics – known as the “Victorines” – would thrive.[46] Other figures such as John of Salisbury (1120-1180), William of Auvergne (1180-1249), Alexander of Hales (1185-1245) would extend Augustine’s legacy further. Though, these thinkers frequently mixed Augustinianism with the philosophy of Aristotle.

The development and interaction of Aristotelian and Platonic traditions is extraordinarily complex. An entire presentation could be devoted to the topic and still not plumb the depths. But, we will make a few comments about it.

First of all, the initial introduction of Aristotle into Neoplatonic thinking goes all the way back to Porphyry, who “added Aristotelian elements” to what he inherited from Plotinus.[47] This is particularly evident in his Isagoge, a commentary of Aristotle’s work The Categories.

Apart from his logic, Aristotle’s corpus was lost to the Latin West during the early Medieval period.

But, except for his Politics, Aristotle was preserved in the Muslim World through this western downturn. He was held in such esteem that simply called “the Philosopher,” and he was reintroduced into Europe from Muslim thinkers such as al-Kindi[48] (801-873), al-Farabi[49] (ca. 870-951), and Averroës (1126-1198), as well as Jewish thinkers like ibn Daud[50] (ca. 1110-1180) and Maimonides.[51]

The wild card was that Islamic philosophers misattributed a volume, which they knew under the title The Theology of Aristotle. This Arabic text – actually a conglomeration of the thought of Plotinus and Porphyry – led Islamic scholars to suppose that Aristotelianism contained elements of Neoplatonism!

St. Thomas Aquinas had drawn from Maimonides and Averroës to “[achieve] an original synthesis of Aristotelian philosophy and Christian theology”[52] In part by modifying Aristotle, Aquinas created a Christian Aristotelianism similar to how Augustine had forged a Christian Platonism. St. Bonaventure (1221-1274), Aquinas’s contemporary, was wary of Aristotle. The so-called “Seraphic Doctor,” Bonaventure, advocated for a return to the Platonism of Augustine, and an ensuing “return to a spiritual union with God,”[53] even drawing upon the Mystical Theology of Dionysius the Pseudo-Areopagite.

‘Heterodox’ Neoplatonic Christianity

But, mention of this latter Dionysian influence drives us headlong into the second flavor – or subsort – of Christian Neoplatonism. This one is a little harder to classify because, to some commentators, it is less obviously Christian in the traditional sense.

It should be noted that flirtations with “heterodoxy” are by no means Medieval novelties. For example, the Alexandrian School of Christianity (mentioned earlier) included Origen (ca. 185-253).

Origen’s orthodoxy is sometimes questioned – or denied – partly on account of his endorsement of now-condemned views, such as the preëxistence of the soul and theological “universalism.”[54]

A popular Catholic apologetics website summarizes this latter view. Origen believed that, in the eschaton, “all people and all angels, even the fallen ones, will return to …[a] pristine spiritual state. They will end up in heaven… In the end, hell …will be empty, and everybody will be saved.”[55]

Occasionally, Alexandrian catechesis is connected to the views of people such as Apollinaris of Laodicea[56] (d. 382) and Eutyches[57] (ca. 380-456), both of whom are remembered for speculative doctrines about Jesus Christ that were declared to be heretical by the leaders of the ancient church.

Two crucial characters in this heterodox Neoplatonic Christianity were the 6th-c. Roman philosopher Boethius (477-524) and the anonymous person referred to as “Pseudo-Dionysius” (ca. 5th-6th c.).

Boethius is mainly remembered for his Latin translations of Greek editions of select works from Plato and Aristotle, as well as his translation of Porphyry’s introduction to Aristotle’s Categories. The upshot of these efforts was that the principal answers to the so-called “Problem of Universals” – a major focus of metaphysics in the Middle Ages – were framed largely by Boethius.

The “Problem of Universals” arose when medieval thinkers contemplated the implications of Plato’s Theory of Forms, which we sketched earlier. You will recall that these issues related to things such as: Is there something that all dogs have in common with each other? To put it another way, when we identify both Fido and Rover as dogs, are we depending on – and referencing – some actually existing “thing” that both Fido and Rover share?

“Realists” answer yes, and thereby commit themselves to the existence of “Natures” or “Universals” such as (what we might call) Dog-ness, Human-ness, etc. Or, are we merely assigning the same word to Fido and Rover –from language conventions or habit? People who take this line are known as “Nominalists,” from the Latin word nomen, meaning “name.” Or… is it something else? Apart from these questions, …

Boethius’s major original work was The Consolation of Philosophy, which he wrote – while in prison awaiting execution – as a dialogue between himself and a personified Spirit of Philosophy or Truth.

Boethius is sometimes regarded as a Christian. Indeed, because he was put to death by the government – allegedly for “treason” – he is occasionally classified as a Catholic Saint. That said, there is scholarly debate over his actual sympathies and over the appropriateness of viewing his death as true martyrdom. On the opposite extreme, some commentators view Boethius as a pagan Neoplatonist and pantheist.[58]

“Pseudo-Dionysius” was a second notable in this ambiguous Neoplatonic stream. He later exerted a profound influence on the Franciscan religious order, through the previously mentioned Bonaventure.

The writings of this figure – whose true identity is unknown – won legions of followers in the Church.

For many years, it was believed that he was the historical Dionysius the Areopagite who is depicted as converting to Christianity in the 17th chapter of a Biblical book titled the Acts of the Apostles.[59]

It was mainly through Dionysius’s influence that an esoteric Neoplatonism made significant inroads in Catholicism. Among Pseudo-Dionysius’s acolytes were, the 9th century scholar John Scotus Eriugena,[60] figures associated with the 11th-12th-c. School of Chartres,[61] and the 13th-century Dominican professor Albertus Magnus.[62] Albert is best remembered as having been the teacher of St. Thomas Aquinas.

We have discussed Albert the Great in several videos, including “Top 10 Gold-Making Alchemists” and “10 Secret Adepts.”

But one of the most influential thinkers to proceed from the Pseudo-Dionysian tradition was Aquinas’s mystical contemporary and fellow Dominican friar, Meister Eckhart (ca. 1260-1328).[63]

Eckhart’s first apologists, pupils, and fellow Dominicans, Henry Suso (1295-1366)[64] and Johannes Tauler (ca. 1300-1361), widely popularized a heavily mystical variety of Neoplatonism that once again verged on pantheism.[65]

This mysticism drew heavily upon the via negativa. You will recall that we sketched this “theology of negation” earlier. It lent itself to a style of contemplation that was showcased – and recommended – in the anonymous, 14th-century tract titled The Cloud of Unknowing.[66]

Thus, a heavily Neoplatonic spiritualism became “prevalent toward the end of the thirteenth century.”[67] It helped to “[undermine the] scholastic rationalism” that arguably reached its zenith in a version of Aristotelianism called “Thomism” – which was the philosophical-religious legacy of Aquinas.[68]

The end of Scholasticism, and the rise of Reformation Protestantism – along with the Renaissance and “Modern” philosophy – is bound up with the work of various Neoplatonic occultists, …

…some of whom we will mention in a moment, and many of whom we have already surveyed in other videos, such as “Top 10 Occultists of All Time” and “10 Mystery Men.”

Here, we will note 14th-c. Augustinian canon Jan van Ruysbrœck;[69] 15th-c. Carthusian monk Denis Ryckel; and German Renaissance humanist and mystic Nicholas of Cusa, also in the 15th century.[70]

This group’s influence extends to the 20th century and beyond where, for example, Meister Eckhart and Nicholas of Cusa would inform the psychiatry of German-Swiss thinker Karl Jaspers (1883-1969).

And self-proclaimed “spiritual guru” Eckhart Tolle, “…whose real first name is Ulrich [Leonard Tölle], …changed his name to Eckhart in a homage to the German spiritual leader Meister Eckhart.”[71]

Non-Christian Neoplatonism

Before moving on to other thinkers who would continue the above-named Neoplatonic tradition(s), we should say something – even if too briefly – about versions of Neoplatonism that were found in the two other so-called “great monotheistic religions.”

Of course, the primary mystical traditions in Islam and Judaism are called Sufism and Kabbalism, respectively. Kabbalah has already come up in past presentations such as “10 Arcane Words” and “Top 10 ‘Sex-Magic’ Cults.”

Even so, we hope to say much more about both streams in future videos. Suffice it here to say that…

…until the Renaissance, the prominent version of Platonism within these two religious traditions was primarily philosophical. This can be seen in the thinking of the 1st-c. Alexandrian-Jewish Middle Platonist Philo Judæus (ca. 20 B.C.– A.D. 50). It is also detectable in the works of the 9th-century polymath Al-Kindi (801-873), called the “father of Arab philosophy,” and in the writings of the 12th-century Spanish-Jewish Halachist and Talmudist Moses Maimonides (1138–1204).

As was stated previously, the latter two were primarily Aristotelians who incorporated Neoplatonic elements into their systems. Predictably, this blend is often called “Neoplatonic Aristotelianism.”

The high-water mark for Islamic Neoplatonism was arguably the work of Avicenna, otherwise known as Ibn Sina (980-1037). In Judaism, one thinks of Avicebrón (ca. 1021-1070).[72]

Having said this, elements of Neoplatonism show up elsewhere in both traditions. For instance, consider that “Al-Fārābī[‘s embrace of] Neoplatonism …paved the way for mysticism to enter Islamic philosophy. …Philosophically, Neoplatonism provide[d] answers to most major questions within the context of Islam, such as how multiplicity came from unity and how corporality emanated from an incorporeal God, as well as explaining the ascending and descending order of beings.”[73]

“Neoplatonism strongly influenced the development of Sufism,” specifically.[74] A major and seminal statement of this perspective – itself largely a reaction against the rationalism of Avicenna – was articulated by “…the towering [11th-12th-century] figure …[al-Ghazali],[75] who rejected philosophy altogether and became the exponent of Sufism alone.”[76]

On a separate trajectory, “there arose Ismā‘īlīs philosophy, which …[combined] Sufi and Hermetico-Pythagorean ideas”[77] without rejecting Neoplatonism.[78]

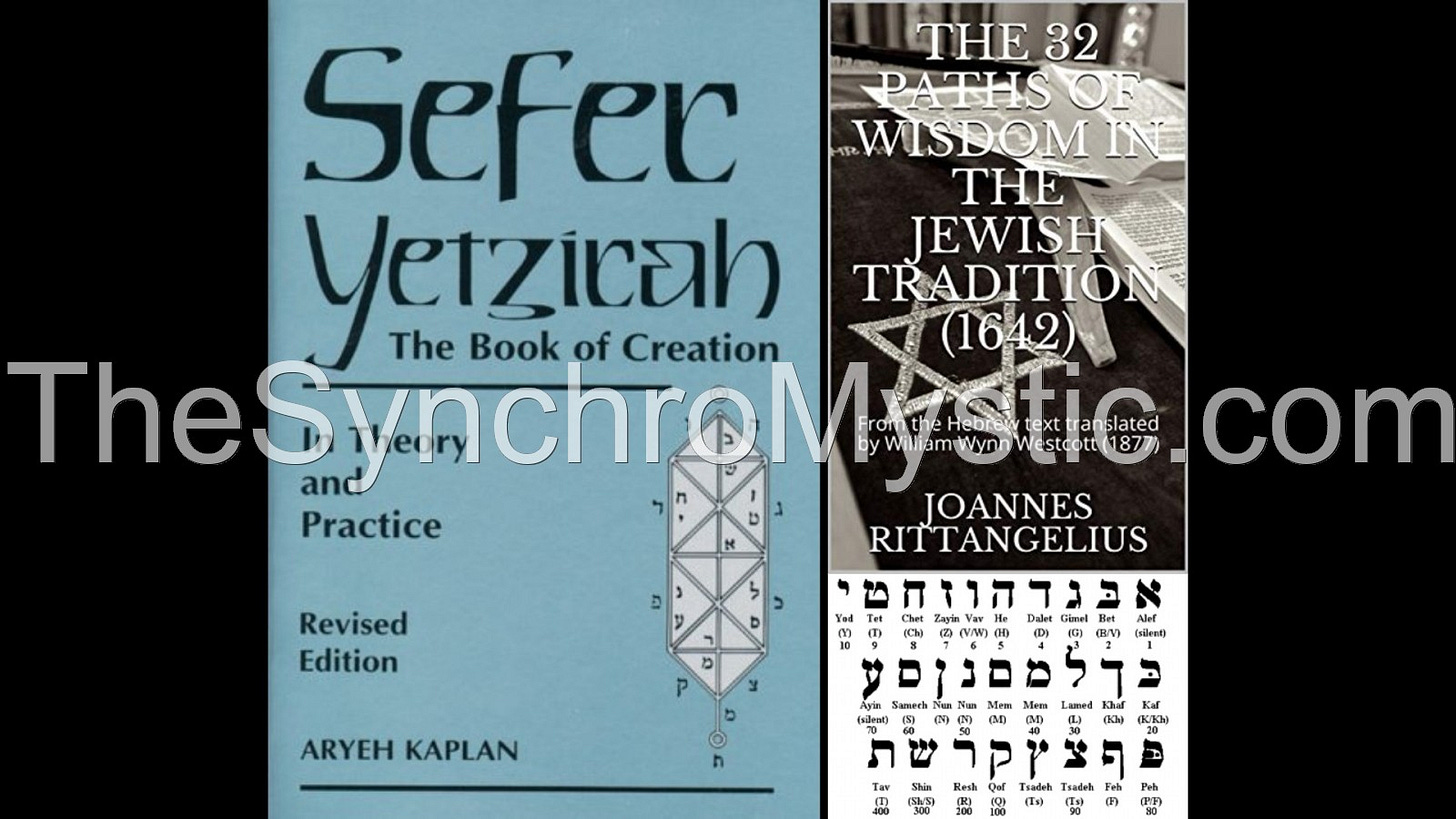

Within a Jewish context, we have the mystical treatise titled Sefer Yetzirah, or “Book of Formation.”[79] Usually dated to around the 4th century, it is a meditation upon the way in God supposedly created the cosmos. In the system of the Sefer Yetzirah, as it was believed to have been revealed to the Patriarch Abraham, God utilized the Hebrew language to create the universe. The unknown author (sometimes asserted to be the 1st-2nd-century Rabbi Akiva ben Yosef) analyzed this alleged procedure into various esoteric letter manipulations.

Some commentators have observed that the so-called “Sephiroth,” or attributes of God, are akin to Plato’s Forms.[80]

And the fact the twenty-two letters have meaningful numerical correspondences sounds an unmistakably Pythagorean note.

19th-century occultist Éliphas Lévi would later associate the Hebrew letters with the twenty-two “Trump” cards of the Tarot.

For a bit more on Lévi, see “Top 10 Occultists,” “10 Arcane Words,” and “10 Secret Adepts.”

Or consider the probable-12th-century text called the Sefer Bahir, or “Book of Illumination.” This work develops a Kabbalistic version of emanation, another concept characteristic of Neoplatonism.[81]

Concerning the monumentally important Sefer ha-Zohar, (“Book of Splendor”), one rabbi writes that the appendix known as the “Hidden Midrash,”[82] “...seems to have its origins in Neoplatonism…”.[83]

Renaissance Neoplatonism

Medieval Neoplatonism morphed into a different shape during the Renaissance. This is partially because streams that had been separated after the division and fall of the Roman Empire, began once again to intermingle. For example, the distinct, Eastern tradition of Neoplatonism that had been preserved in the Byzantine Empire by Greeks such as Michael Psellus[84] (1018-1075) and John Italus[85] (fl. 1070-1080) were introduced in the West.[86]

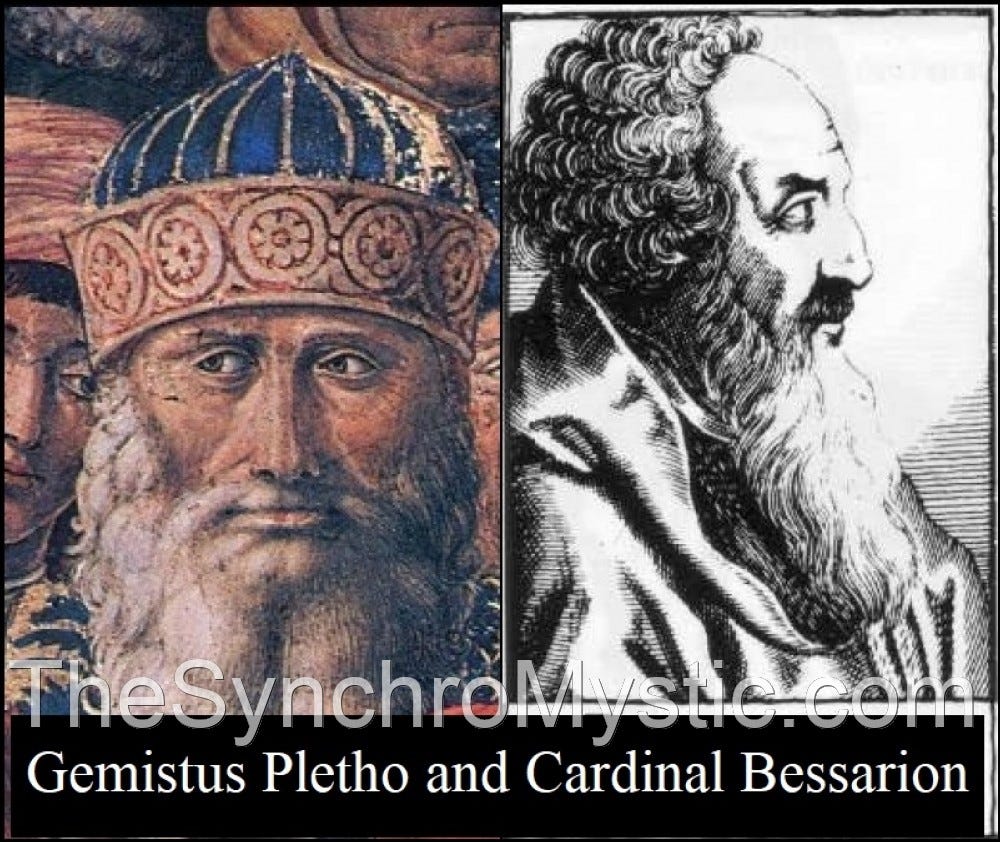

Some key people in this transmission were the Greek figures “Pletho”[87] (ca. 1355-1452), Manuel Chrysoloras (1355-1415), and Cardinal Bessarion (1403-1472).

Following the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in the year 1453, and partially through the instrumentality of Pletho, Constantine Lascaris (1434-1501), and others, Neoplatonism’s center of gravity shifted to Italy.

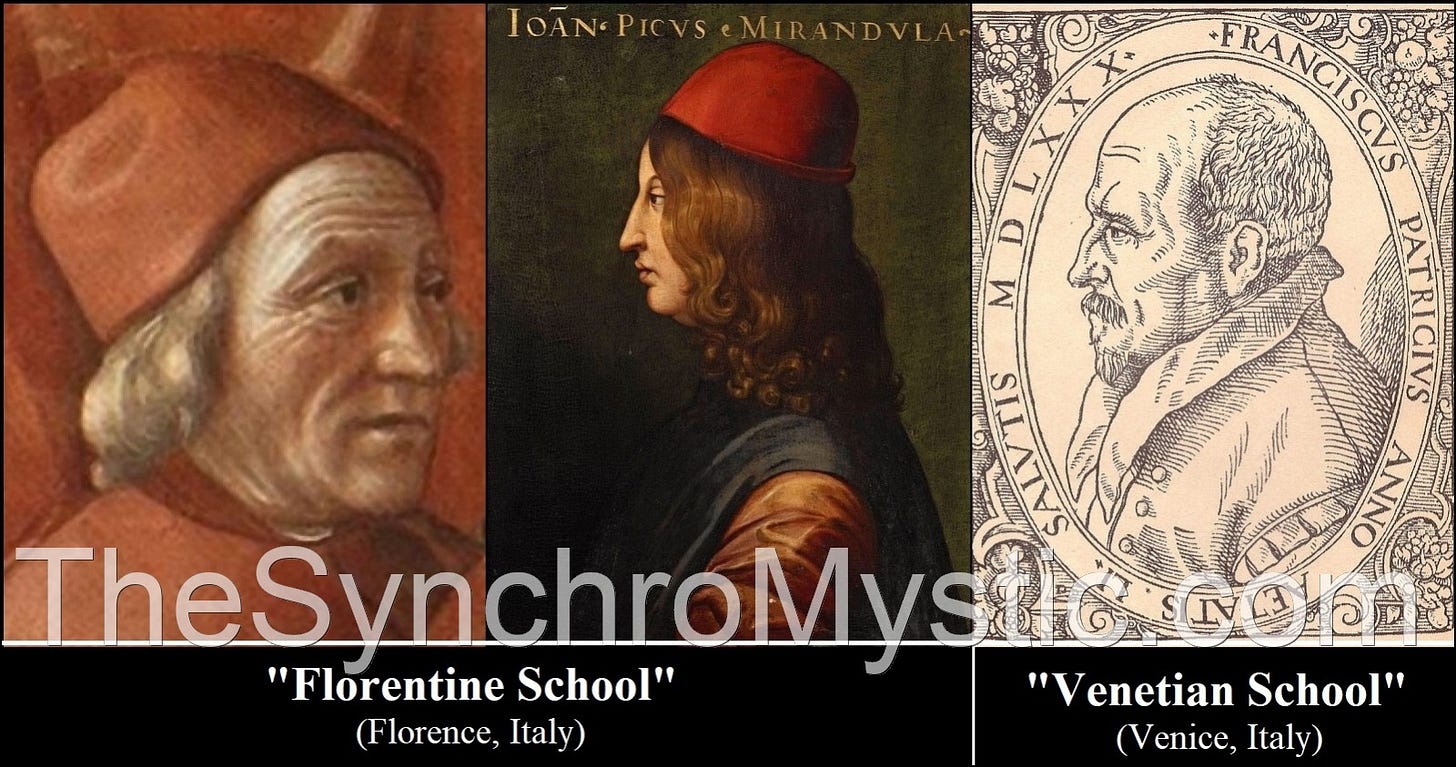

There, in the so-called “Florentine School,” Marsilio Ficino (1433-1499) and Pico della Mirandola (1463-1494) were dominant.

Pico was not a thoroughgoing Neoplatonist. He was a syncretist who seems to have been chiefly motivated to try to combine elements from various belief systems – including Aristotelianism and Platonism – with which he was familiar. Pico’s main “claim to fame” rests on his introduction of Jewish-mystical elements into Catholicism creating the amalgam known as “Christian Cabala.”

But for the shadowy figures lurking behind both Pletho and Pico, see “10 Mystery Men.”

Elsewhere in Italy, the Venetians Francesco Giorgi (1466-1540) and Franciscus Patricius (1529-1597) communicated the Neoplatonic torch to England, Germany, and – within Italy itself – Rome.

Key components of this Renaissance Neoplatonism were:

(1) the adoption (by people like Ficino and Giorgi) of a hierarchical view of the universe;

(2) the theorizing of “correspondences” that would underlie a plethora of “ceremonial,” “mathematical,” “natural,” and “sympathetic” types of magic;

(3) and the renewal of attempts to synthesize a new religion – sometimes described as a recovered “true form” of Christianity – by combining insights from all then-known systems. The synthesis rested on the conviction that all religions flowed from the same, primeval source and that they all – properly interpreted – articulated one coherent philosophical-theological perspective.

This syncretism was typified by Pico, who sought to harmonize Neoplatonic Christianity with the philosophies of Aristotle and Plato, as well as with Hermeticism and the Kabbalah.[88]

Spanish Kabbalistic mysticism had only then been introduced into Italy by way of rabbis escaping the Jewish expulsion ordered in 1492 by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella.[89]

For more on that episode – including some behind-the-scenes operators – see “10 Mystery Men.”

Regardless, Neoplatonism made its way to the Papal States, where it was promoted by Vatican “insiders” such as Italian littérateur and Knight of Malta, Cardinal Pietro Bembo.

At this point, there seems to be yet another “split.”

‘Academic’ Neoplatonism

Along one line, there’s a string of those who were predominantly academics.

Chief among these are the Cambridge Platonists, including Henry More (1614-1687) – who was a descendant of English Catholic saint and martyr Thomas More (1478-1535).[90]

You will recall that, along with Desiderius Erasmus and John Colet, Thomas More is routinely classed as a so-called “Oxford Reformer,” a group of humanist scholars loosely associated with Oxford in England. They are thought of as “reformers” in the sense that they championed approaches to Bible interpretation (and other matters) that marked a departure from Medieval thought.[91]

As briefly mentioned in “10 Mystery Men,” John Colet was – for a time – in close contact with Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa.

Agrippa is so well-known and influential that we initially profiled him in our video titled “Top 10 Occultists of All Time.”

Additionally, Thomas More helped to introduce the British Isles to the thought of seminal “Christian Cabalist,” Giovanni Pico della Mirandola,[92] whom we just mentioned.

According to historian Frances Yates, one distinguishing feature of Cambridge Platonism was that these new, professorial Neoplatonists distanced themselves from hermeticism. First and foremost, hermeticism was a cluster of stories – collectively termed the Corpus Hermeticum.

According to legend, a figure named Hermes Trismgestus, or “Thrice-Great Hermes,” had mastered the “three parts of wisdom” – a trio of occult sciences consisting of alchemy, astrology, and magic.

For more on this, see “10 Arcane Words” and “10 Gold-Making Alchemists.”

Hermetic lore held that Hermes was a primordial figure. The character was frequently identified with various mythical deities, among them the Egyptian god Thoth.

In numerous books offered for sale on Amazon.com, not to mention in articles on scores of websites (of varying reliability), one can still read claims such as that, according to legendary Egyptian priest Manetho, Hermes wrote 36,000 books, or that he dates to some astounding time, such as 36,000 B.C.!

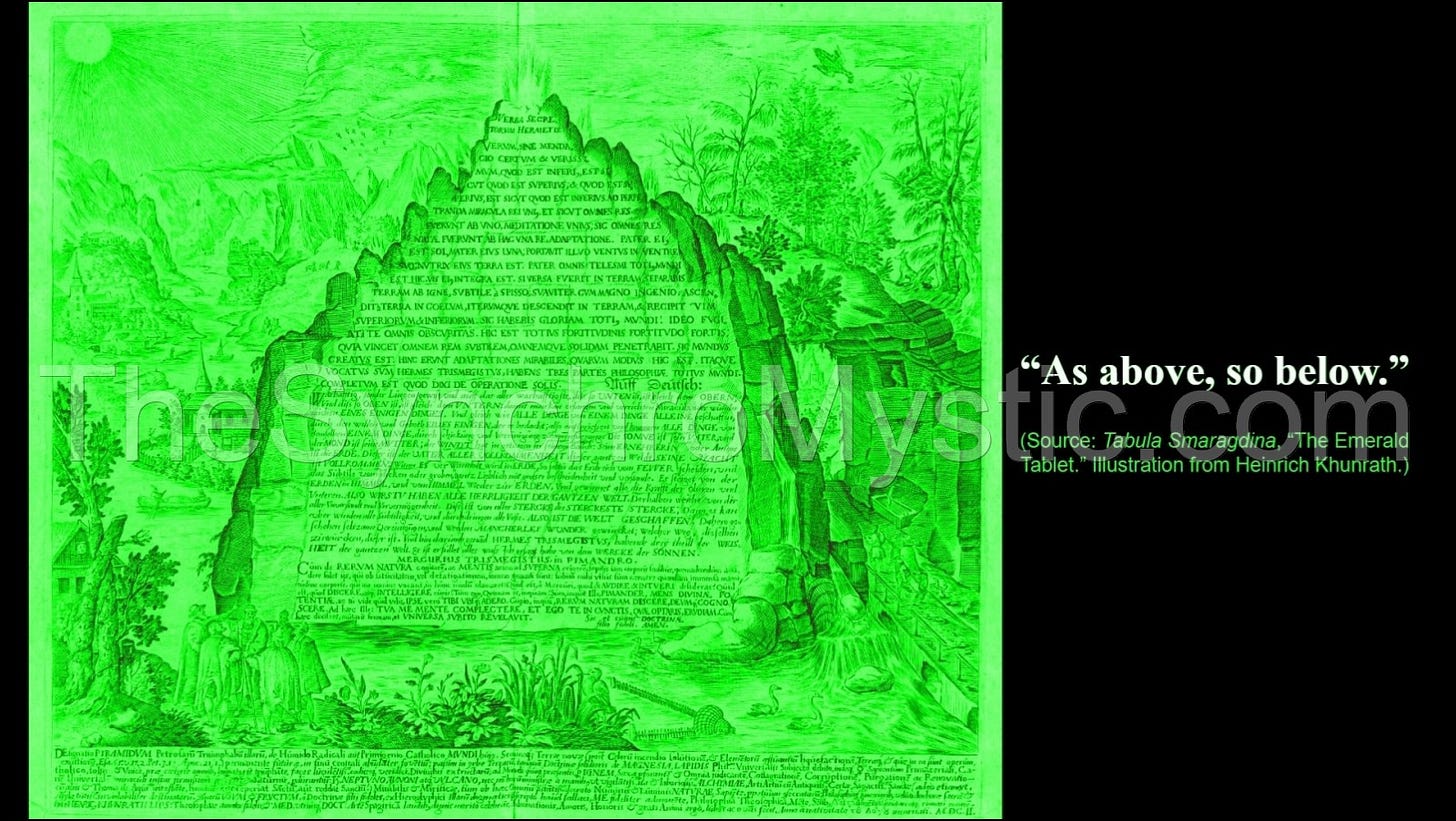

A variation on this theme concerns the so-called “Emerald Tablet.”[93] This is a short text – just a collection of a dozen or so sentences, really – that is believed to set forth what is often taken to be the essence of the Hermetic outlook: the alchemical maxim “as above, so below.”

This tantalizing and cryptic phrase is typically explained in terms of an elaborate theory of “correspondences.” This is the doctrine that various associations, or connexions – whether symbolic or otherwise – exist among the levels of reality (for example, between the celestial realm of the stars and commonplace world of human society, or even your individual anatomy).

Because this hermetic dictum asserts – or assumes – the existence of a hierarchical universe, it can be fitted quite nicely into an overarching Neoplatonic worldview.

And, for a long time, this was believed – even by the highly educated. The previously mentioned Ficino, for example, expended considerable effort translating several hermetic books at the behest of his patron Cosimo de’ Medici (1389-1464). Ficino even temporarily sidelined a massive project of translating the works of Plato. He did this because both he and Cosimo believed that Hermes was an even more ancient and important authority than Plato.

Ficino’s translations of the hermetica were expanded upon by the purported magician and Neoplatonist Lodovico Lazzarelli (1447-1500).[94]

Giordano Bruno (1548-1600) was perhaps the last notable figure of the period to have been Hermetic in the original sense of seeming to take the story of Hermes literally. Incidentally, Bruno’s associations may have brought him into the orbit of Queen Elizabeth I’s royal astrologer, the sorcerer John Dee, whom we highlighted in our “Top 10 Occultists” video.[95]

In any event, Bruno has the dubious distinction of being one of the last people burned at the stake for heresy, by order of the Roman Inquisition.

A tangent academic line may also be detected through Bruno’s influence.[96] For example, in 1714, the famous “Continental Rationalist” German philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716) set forth a metaphysical theory centering upon the curious notion of a “monad” – which term had been coined by Bruno in 1591,[97] possibly as an adaptation from concepts such as John Dee’s Monas Hieroglyphica.

In the year 1614, about a decade and a half after Bruno’s execution, a Swiss-born philologist named Isaac Casaubon published a book in which he argued that the Corpus Hermeticum was unlikely to have had the kind of provenance that would have placed its author approximately in the late stone age. Rather, according to his analysis of the language and style of the texts, Casaubon estimated the probable date of composition sometime around the 3rd or 4th centuries A.D.

While even this time is early by conventional, historical measures, Casaubon’s thesis does tend to deflate the pretension that Hermetic doctrines hearken back to misty expanses in human prehistory.

In other words, Casaubon believed that the much-revered Hermetic stories were, at best, a kind of folklore. Perhaps they were concocted in an attempt to popularize and make more relatable some of the more intricate philosophies – like ancient Neoplatonism – that grew up in the intellectually tumultuous Greco-Roman period and that wouldn’t appeal to people who aren’t looking to major in philosophy.

Those academics that accepted Casaubon’s much later date of the Corpus Hermeticum – including, in Yates’s opinion, the Cambridge Platonists – didn’t have much reason to esteem Hermes. As a result, many Neoplatonists – and most scholars, generally – have eschewed hermeticism from then on.

‘Eclectic’ / ‘Folk’ Neoplatonism

But, there is a second line of broadly allied thinking that can be traced back at least to a 16th-17th-c. German shoemaker named Jakob Böhme (1575-1624; also spelled Jacob Boehme).

According to the late historian Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke, Böhme was steeped in the thought of the Swiss alchemist and experimental physician who was born Theophrastus von Hohenheim but is probably better known as “Paracelsus” (1493-1541).

We covered Paracelsus in greater detail in “Top 10 Gold-Making Alchemists.”

And we sketched the history of his mysterious mentor, Johannes Trithemius, in “10 Mystery Men.”

Some commentators do suggest that there is a species – or at least an analog – of Neoplatonism to be found in Paracelsus and Böhme.[98] For example, Antoine Faivre compared Paracelsus to “the Neoplatonists Plotinus and Porphyry,” writing that they shared a “qualitative concept of time, ‘which flows in a thousand ways,’ [with] each individual thing possessing its own rhythm.”[99]

At the very least, Böhme is “Neoplatonic” in the sense that he follows generally in the Plotinian tradition by practicing meditative and mystical “methods that [promise to] permit gaining access to a supersensible reality…”.[100]

The ideas of Paracelsus and Böhme arose in non-academic, Protestant-Lutheran contexts.[101] This certainly is not to say that orthodox Lutherans approved! It is noteworthy that Paracelsus was primarily educated by his father, and from books such as those written by the mysterious Benedictine monk and purported magician, Johannes Trithemius (1462-1516) mentioned moments ago.

We treated Trithemius in much greater depth in “10 Mystery Men.”

Similarly, becoming a cobbler didn’t require a formal education. Like Paracelsus, Böhme’s intellectual formation occurred largely outside of the control of the university system or of “organized religion.”[102]

Instead, while he apprenticed in his trade, he filled odd hours reading the Bible and interacting with Paracelsian physicians.[103]

Still, the “blueprint” for Paracelsian and Böhmian cosmologies is sufficiently similar to what we have been considering to prompt Goodrick-Clark to remark that it is reminiscent of “the emanationist Neoplatonic philosophy of Plotinus”.[104]

And we would expect this given that one can draw a line from the thinking of Plato and Plotinus, through Marsilio Ficino and Pico della Mirandola, to Johannes Trithemius who, as we just heard, exerted a tremendous, formative influence upon Paracelsus.[105]

Paracelsus is then picked up by Belgian alchemist Gerhard Dorn[106] (1530-1584), who would later influence pioneering Swiss depth-psychologist and psychoanalyst, Carl Gustav Jung (1875-1961).

Paracelsus’s thought informs the that of German theologian Valentin Weigel[107] (1533-1588).

For more on that potent name – which also shows up in Rosicrucianism – see “Be My Valentine.”

Paracelsus also shaped German hermeticist Heinrich Khunrath (ca. 1560-1605), whose Amphitheatrum Sapientiæ Æternæ (1595) functions as a bridge from alchemy to Rosicrucianism in Germany as well as to the occult tradition in England.

The latter includes, preëminently, Queen Elizabeth I’s royal astrologer and reputed sorcerer, John Dee. But Khunrath may also, in the words of Professor Antoine Faivre, have “set Boehme on his path.”[108]

Paracelsus’s elemental speculations would be furthered by German alchemist Oswald Croll[109] (ca. 1563-1609) and Belgium chemist Jan Baptist van Helmont (1580-1644), whom we reference in “Top 10 Gold-Making Alchemists.”

Böhme would exert a tremendous influence on the direction of the so-called Radical Reformation, a point which we hope to develop in a forthcoming video.

Otherwise, “Behmenism,” as this folk variety of Neoplatonism was called in England, also seems to have set the stage for the major, 17th-c. esoteric cultural phenomenon known as “Rosicrucianism.”

Rosicrucianism, in turn, would inspire Englishmen, such as the antiquarian Elias Ashmole, who came in at the ground floor of what would, in the 18th century, be recognized as speculative Freemasonry.

Both Rosicrucianism and Freemasonry – in both its three-degree “Craft” variety, and in various “appendant,” high-grade esoteric systems – are such large topics that I cannot do them justice here. Instead, I intend to create follow-up presentations treating these – and other – topics with greater care.

For the time being, I’ll simply note that, even if his name is less familiar today, Böhme’s influence has by no means completely waned. The popular spiritual writer Eckhart Tolle (born Ulrich Leonard Tölle), mentioned moments ago, credits the idiosyncratic artist Bô Yin Râ (1876-1943) with inspiring his path.[110] Would you be surprised to learn that Bô Yin Râ, a 19th-c. painter whose real name was Joseph Anton Schneiderfranken, was partly inspired by – guess who? – Jacob Böhme.[111]

According to some observers,[112] Tolle’s worldview is the contemporary embodiment of the sort of syncretism that has occupied us throughout this study and which he arguably inherited from his immediate Theosophical and New-Age predecessors – people like H. P. Blavastsky,[113] G. I. Gurdjieff,[114] and, more recently, Marilyn Ferguson.[115]

Conclusion

To say that Plato’s influence on Western culture and thinking has been enormous would be an understatement of gigantic proportions. His philosophy – both as Plato articulated it, and as it would be developed by the Neoplatonists – beginning with Plotinus and Porphyry – has profoundly shaped many worldviews.

Serious observers – both of the occult, specifically, and of the history of thought, generally – will find that it is worth familiarizing themselves with the basic contours of the Platonic / Neoplatonic traditions.

Literature students, also, will be served by a working knowledge of Neoplatonism. For example, consider the Florentine poet Dante Alighieri (1265-1321), whose monumental Divine Comedy (ca. 1320) was made a leitmotif in Dan Brown’s Inferno (2013) and Ron Howard’s 2016 film adaptation.

Although “…Aquinas and Augustine …[are] Dante’s immediate philosophical ancestors …, it is also clear that [his epic] poem fuses themes from Plato, Neoplatonism, and the Islamic tradition, especially that of Avicenna.”[116]

As we saw, Neoplatonism is relevant to gaining a full understanding of key Renaissance personalities, such as Pletho and Marsilio Ficino, who resuscitated it and blended it with humanism.

From Italy, it spread all over Europe. The Italian diplomat and writer Baldassare Castiglione (1478-1529) wrote about “Platonic love” in his instructional manual, The Book of the Courtier (ca. 1528).

Castliglione, whether directly – or indirectly, via the English translation (1561) of Sir Thomas Hoby (1758-1835), along with Bembo and Ficino, seems to have shaped the Shakespearean corpus.

Besides the “Bard,” Neoplatonic elements also figure in the works of English poets Edmund Spenser (1552-1599, John Donne (1572-1631), and many others.

But, Neoplatonism is also detectable in 17th-century institutional, university settings, for instance, in the activity of the Cambridge Platonists.

It crops up again during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, in the Romantic movement, for example, with English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge and translator Thomas Taylor.

William Blake (1757-1827) is yet another mentionable in whose work Neoplatonism is given artistic expression, for example in Blake’s illustrations for an edition of Dante’s Divine Comedy.

On Blake’s more sex-magical interests, and the broader context, see our previous video on that topic.

According to academic Arthur Versluis, the traditions of Indian religion and Neoplatonism coalesced in 19th-century Transcendentalism – an American version of Romanticism famously associated with writers Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau.[117]

According to author Cathy Gutierrez, “…Spiritualism” – connected to reputed “healers” and “mediums” such as Andrew Jackson Davis, the Fox sisters, and Cora Hatch – “may be understood as a cultural expression of Neoplatonic Renaissance thinking refurbished for American use.”[118]

Some critics find the impress of Plotinus in the works of British poet William Butler Yeats (1865-1939), best known in occult circles for his association with the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn.

Of course, there is popular fantasy writer C. S. Lewis (1898-1963),[119] who wrote The Chronicles of Narnia (1950-1956), several installments of which were recently made into movies.

Lewis also penned numerous non-fiction works defending belief in Christianity, to which he was warmed up by his friends and fellow novelists and professors Hugo Dyson (1896-1975)[120] and J. R. R.[121] Tolkien (1892-1973). The latter is best-known for his fantasy novels The Hobbit[122] and The Lord of the Rings.[123] Tolkien had converted to Catholicism in 1900,[124] But James Webb characterized Lewis’s spiritual views as “a Neo-Platonic [sic] form of Christianity…”.[125]

As a SynchroMystical aside, we can’t help mentioning that C. S. Lewis – along with Aldous Huxley, author of dystopian classic Brave New World[126] – “just happened” to die on the same day that U.S. President John Fitzgerald Kennedy was assassinated.

We have so far tackled that fateful day in two videos (1 & 2), to which we may add more later.

Wrapping up the present topic, Neoplatonism may be a precursor to the “Process Philosophy” of Alfred North Whitehead and Charles Hartshorne, as well as the spin-off Process Theology movement associated with people such as John Boswell Cobb and David Ray Griffin.[127]

Even the most basic tenet of Platonism – insistence upon the metaphysical reality of Forms – persists in some currents of Western philosophy today. You’ll find it, for instance, in German logician Gottlob Frege’s notion of a “Third Realm” – beyond the realms of the physical world and our mental states – and in British ethicist G. E. Moore’s “non-natural properties,” which he offers as his ground for moral truths.

In fact, it arguably shows up in any thinker (in at least a low-grade form) who endorses an idea of really existent “abstract objects,” as distinct from concrete objects in space and time. This would include such people as Kurt Gödel, Bertrand Russell, and Willard van Orman Quine.

Numerous other contemporary scholars – Diogenes Allen, Simon Blackburn, Myles Burnyeat, Richard Kraut, Melissa Lane, S. Sara Monoson, Alexander Nehamas, Leo Strauss, A. E. Taylor, and Gregory Vlastos – being notable examples – have found the careful study of Plato to be worthwhile …

…even if, as with Karl Popper, they take a critical posture towards him.

And, of course, Platonism, in one variety or other, has resonated with religious believers (of many persuasions), who frequently find it that it coincides with – or even expresses – doctrines that posit otherworldly entities, such as angels and God, and hidden realms, such as heaven and hell.

Interested readers may wish to note that we have a shorter version of this study –along the lines of “Gnosticism Explained in 5 Minutes.” That, five-minute edition of “Neoplatonism” is HERE.

But if you found something of interest in this article, please consider watching the associated video (HERE). And if you think someone else would appreciate it, please share the link! Thanks for reading!

[Note: Book titles within this document may have Amazon-affiliate hyperlinks. Purchases assist our efforts to create high-quality resource materials. Your patronage is appreciated!]

[1]Bryan Magee, The Great Philosophers: A History of Western Philosophy, “Episode 5: Bryan Magee talks to Anthony Quinton about Spinoza and Leibniz,” BBC Worldwide, originally broadcast in 1987; republished on DVD, Princeton, N.J.: Films for the Humanities & Sciences, 2002-2004; posted as “Spinoza & Leibniz – Bryan Magee & Anthony Quinton (1987),” YouTube, Mar. 8, 2022, <

>.

[2]Quinton’s contemporary, Freemasonic scholar Manly Palmer Hall, thought that the Neoplatonic conception of divinity was something like “All Truth.”

[3] William F. Lawhead, A Voyage of Discovery: A Historical Introduction to Philosophy, 2nd ed., Belmont, Cal.: Wadsworth, 2002, p. 102; “not just a Platonic philosophy of religion, but a genuinely religious philosophy.” Ibid.

[4]See, e.g., Milton D. Hunnex, Chronological and Thematic Charts of Philosophies and Philosophers, Grand Rapids, Mich.: Academie Books; Zondervan Publ. House, 1986, chart #4, n.p.

[5]A. N. Whitehead, Process and Reality, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010, p. 39, <https://books.google.com/books?id=uJDEx6rPu1QC&pg=PA39>.

[6]The dialog is available online: e.g., <http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/parmenides.html>.

[7]<http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/republic.html>.

[8]Here, we’re thinking mainly about Egyptian and Persian mythology and paganism, but perhaps also some sort of tradition from India. Porphyry writes about Plotinus that “stayed continually with Ammonius and acquired so complete a training in philosophy that he became eager to make acquaintance with the Persian philosophical discipline and that prevailing among the Indians.” Plotinus, Ennead, Volume I: Porphyry on the Life of Plotinus, Enneads I, <https://www.loebclassics.com/view/LCL440/1969/volume.xml>; cf. Plotinus: Porphyry on the life of Plotinus and the order of his books. Enneads I, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Univ. Press, 1966, p. 9, <https://books.google.com/books?id=sVYNAQAAMAAJ>.

[9] In the Greek, telos – whence we get “teleology.”

[10]Sometimes, “emanation” is used to designate only the “downward” flow, while the “return trip” (so to speak) is labeled epistrophe. Other times, “emanation” is used as a generic term for either “direction.” In this latter case, the descent is called prohodos and the ascent is epistrophe. See, e.g., Gary Zabel, “Emanation and Triads,” class notes, Phil 281b, Univ. of Mass., Boston, Feb. 1, 2000, <http://www.faculty.umb.edu/gary_zabel/Courses/Phil%20281b/Philosophy%20of%20Magic/Arcana/Neoplatonism/Emanation%20and%20Triads.htm>; citing R. T. Wallis, Neoplatonism, 2nd ed., Indianapolis, Ind.: Hackett Publ. Co., 1995.

[11]Christian Wildberg, “Neoplatonism,” Edward Zalta, ed., Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Winter 2021, <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2021/entries/neoplatonism/>. The quotation continues: “ …—with the exceptions of Epicureanism, which they roundly rejected, and the thoroughgoing corporealism of the Stoics.” Ibid. Also, as stated, the logos concept derived from the Stoics, who had obtained it from Heraclitus.

[12]Cf. “Aristotelianism,” Britannica, <https://www.britannica.com/topic/Aristotelianism/Relationship-to-Neoplatonism>.

[13]See, e.g., Porphyry’s Isagoge.

[14] Lawhead, op. cit., p. 102.

[15]Some writers find it useful to distinguish theurgy from goetia. When this is done, “goetia” is typically used to talk about kinds of so-called “black magic” that generally involve summoning or “invoking” demons or other spirits, and that verge on darker practices such as necromancy. “Theurgy,” then, would designate “white magic.” The demarcation is not a little murky, especially since some later magicians (notably, John Dee) would invoke angels using Kabbalistic and Pseudo-Dionysian formulæ and yet insist the occupation was holy and white-magical.

[16] Edward J. Watts, City and School in Late Antique Athens and Alexandria, vol. 41, Berkeley, Cal. & Los Angeles: Univ. of Cal. Press, 2008, p. 192, <https://books.google.com/books?id=MKolDQAAQBAJ>. Continuing: “Hypatia too seems to have had little interest in the teaching of Iamblichus.” Ibid.

[17] Lawhead, op. cit., p. 105.

[18] Lawhead, op. cit., p. 113.

[19] Lawhead, op. cit., p. 113. Additionally: “Plato’s creator (the Demiurge) had to consult the pre-existing Forms when imposing order on a pre-existing matter.” Ibid. Just for completeness, the other logical possibility is that matter has always existed; matter is simply ex Materia. (“out of [pre-existing] matter”). Creation ex Materia is arguably taken up by several forms of Gnosticism, where it is conjoined with Plato’s Demiurge yielding the notion that a being – somehow “lesser” than the “highest deity” – cobbled the cosmos together out of building blocks that were already floating around. Since Gnostics are routinely read as dualists – believing there were two, irreducible substances: matter and spirit – they are usually said to have thought that this activity on the part of the Demiurge displayed his foolishness, ignorance, or malevolence. After all, the received opinion has it that Gnostics associated the material world with evil and the spiritual realm with good.

[20] Or the Good, Plato’s highest Form.

[21] At least, insofar as the One is taken to be divine.

[22] This seems clearly to have been stated in the Second Book of Maccabees (chapter 7, verse 28), where readers are instructed: “[L]ook at the heavens and the earth and see all that is in them; then you will know that God did not make them out of existing things. In the same way humankind came into existence.” United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2 Maccabees, <https://bible.usccb.org/bible/2maccabees/7>.

[23] This coming to be out of nothing did not just “happen” to occur – with no cause. It was the creative choice of a personal God. Traditionally, Christian thinkers – at least, those who have considered the issue – held that God could have opted to create something different – or even to refrain from having created anything at all. Not so, the One.

[24]Interestingly, Julian also supported the rebuilding of the Jewish temple.

[25] Karl Hoeber, “Julian the Apostate,” Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. 8, New York: Robert Appleton Co., 1910, <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/08558b.htm>.

[26] “Theon [of Alexandria] may have kept Iamblichan influence out of his curriculum with a certain amount of pride. Hypatia too seems to have had little interest in the teaching of Iamblichus.” Edward J. Watts, City and School in Late Antique Athens and Alexandria, Berkeley, Cal. & Los Angeles: Univ. of Cal. Press, 2008, p. 192, <https://books.google.com/books?id=MKolDQAAQBAJ>.

[27] “The school of Athens developed Neoplatonism in theological, but anti-Christian directions, most notably in the work of Proclus in the 5th century. In Alexandria, however, a blend of Neoplatonic and Christian elements took place [sic], at its most developed in the work of Boethius.” Simon Blackburn, Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy, Oxford and New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1996, pp. 258-259.

[28] Lawhead, op. cit., p. 114.

[29] Around the 5th century A.D.

[30] Lawhead, op. cit., p. 142.

[31]This school, which was heavily Platonic and generally embraced an allegorical reading of the Bible, is usually contrasted with a competing school, centered at Antioch in Syria, which certainly favored hermeneutical literalism and may also have tended more toward Aristotelianism. Like its Alexandrian counterpart, the Antiochene School had its share of generally orthodox thinkers – such as Diodore of Tarsus and St. John Chrysostom. But it also produced people like Theodore of Mopsuestia, whose writings were long considered suspect. And Antioch saw its share of declared heretics, such as Arius and Nestorius.

[32] Clement was taught at the School in Alexandria by Pantænus (d. ca. 200) and is known for his Stromata (“Miscellanies”).

[33] Athanasius opposed Arius at Nicæa (or Nicea).

[34] Cyril opposed Nestorius at the Council of Ephesus and is sometimes blamed for the murder of Hypatia, q.v.

[35]It is possible to read Augustine’s preoccupation with various biblical themes – such as the fall of humankind, predestination, and the notion of a “dead” human will that requires divine empowerment to choose the good – as his attempt to systematize a Christian theology along (neo)Platonic lines. This is because, in Neoplatonism, the visible world is descended (i.e., fallen) from the One, and the “seeds of the logos” (logoi spermatakoi) permeate lower spheres of reality. The differences, though, are at least as important as the similarities. For example, in Neoplatonism, the lowly state of materiality is due to its metaphysical dislocation from the One. In Augustine, the human fall is construed ethically and is the result of humanity’s decision to turn from God (resulting in a state of moral derangement that John Calvin would much later develop into the Calvinist doctrine known as “Total Depravity”).

[36] Whether Augustine had evidence for or against the existence of Manichæan sex rites is an open question. We suggest that he did in the aforementioned presentation. But Manly P. Hall demurs, writing: “St. Augustine, who had an intimate knowledge of the sect, made no such accusations. His temperament would have inclined him to do so had there been any reasonable grounds.” The Adepts in the Western Esoteric Tradition: Orders of the Great Work, reprint ed., Los Angeles: Philosophical Research Society, 2013 [orig. 1949], p. 13.

[37] He was primed via the works of the Middle Platonist, Apuleius (ca. 124-170). Augustine’s blending of the Biblical-historical doctrines of Christianity with Neoplatonism was prefigured by the 4th-century pagan Gaius Marius Victorinus, who converted to Catholicism.

[38] “Ahriman,” U.X. L. Encyclopedia of World Mythology; archived online at <https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/ahriman>. “Zoroastrianism views [the finite deities] Ahriman and Ahura Mazda as locked in an enduring conflict. …Ahriman …, also known as Angra Mainyu …, was the spirit of evil and darkness … Ahriman is contrasted with Ahura Mazda, the supreme creator of order and goodness. In the Islamic religion, Ahriman is identified with Iblis, the devil.” Ibid.

[39] This is why achieving fullness of being is construed as becoming identical with or merging into the One. The One has perfect fullness of being. Whatever “else” has perfect fullness of being is indifferentiable from the One.

[40] “Augustine of Hippo,” New World Encyclopedia, <https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Augustine_of_Hippo>.

[41] Plato termed this process anamnesis.

[42] Chapt. 9, verse 27; New Intl. Version.

[43] “Augustine of Hippo,” loc. cit.

[44] Or, more precisely, she thinks of herself as transcending the illusions of disconnexion, division, and separation; she rediscovers the genuine overarching – or underlying – unity with the divine that has always existed unnoticed. This “rediscovery” is simultaneously a development and an echo of Plato’s doctrine of anamnesis, whereby humans were thought to have knowledge by “remembering” Ideas from a past life – or, from a time before our physical births during which we had unfettered access to the Platonic Forms.

[45] One might also think of the Benedictine-Cistercian, William of Saint-Thierry (ca. 1075–1148).

[46]These included Hugh of St. Victor (1096-1141), Richard of St. Victor (d. 1173), Thomas of St. Victor (ca. 1200-1246), and Walter of St. Victor (d. ca. 1180).

[47] Blackburn, op. cit., p. 258.

[48] A.k.a. Alkindus.

[49] A.k.a. Alpharabius.

[50] A.k.a. Abraham ben David Halevi, or “Rabad I.”

[51] A.k.a. Moses ben Maimon, or the “Rambam.”

[52] Thomas F. O’Meara, “Thomism,” Encyclopedia Britannica, <https://www.britannica.com/topic/Thomism>.

[53] Blackburn, op. cit., p. 46.

[54] This was termed apocatastasis, meaning “a restoration.”

[55] Karl Keating, “Why wasn’t Origen, the Most Prolific Writer of Christian Antiquity, Canonized?” Catholic Answers, n.d., <https://www.catholic.com/qa/why-wasnt-origen-the-most-prolific-writer-of-christian-antiquity-canonized>.

[56] Apollinarism (along with Semi-Arianism) was condemned at the First Council of Constantinople in 381.

[57] Eutychianism (with other forms of “monophysitism”) was condemned at the Council of Chalcedon in 451.

[58] See Blackburn, op. cit., p. 46.

[59] See, esp., verse 34.

[60] Also known as “John the Scot” (though he was from Ireland) or the Latinized Johannes Scotus Erigena.

[61]E.g., Bernard de Chartres. (See “Bernard de Chartres,” Britannica, <https://www.britannica.com/biography/Bernard-de-Chartres>.) But not John of Salisbury, who was already mentioned, above.

[62] See, e.g., Albert’s Super Dionysii Mysticam, Theologiam Et Epistulas (“On the Mysticism, Theology, and Epistles of Dionysius”).

[63] Despite his Neoplatonism, Eckhart von Hochheim, supposedly born Johannes Eckhart, was nonetheless influenced by Aristotlianism. Sometimes, these influences dovetail. E.g., Eckhart’s godhead (Deitas) was unknowable – as with the Neoplatonic One. Predictably, it also “escaped any becoming” (Faivre, op. cit., p. 43), and therefore lacked any unrealized potential, as with Aristotle’s “Prime Mover.”

[64] Or Heinrich von Suso.

[65] That this germinated within the Dominican Order is interesting. After all, the Dominicans had been instrumental prosecuting the so-called Albigensian (Cathar) Crusade (1209-1229) and during the Episcopal-Papal Inquisitions.

[66] Middle English: The Cloude of Unknowyng.

[67] Lawhead, op. cit., p. 195.

[68] Lawhead, op. cit., p. 195.

[69] Or Jan (or John) van Ruusbroec.

[70] I intend to further investigate figures such as Walter Hilton and Julian of Norwich.

[71] Ether Walker, with Photini Philippidou, “Eckhart Tolle: This Man Could Change Your Life,” Independent (U.K.), Jun. 21, 2008, <https://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/profiles/eckhart-tolle-this-man-could-change-your-life-850872.html>.

[72] Solomon ibn Gabirol, or Ibn Gabirol for short.

[73] Mehdi Aminrazavi, “Mysticism in Arabic and Islamic Philosophy,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Spring 2021 ed., Edward N. Zalta, ed., <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2021/entries/arabic-islamic-mysticism/>.

[74] Kamuran Godelek, “The Neoplatonist Roots of Sufi Philosophy,” The Paideia Archive: Twentieth World Congress of Philosophy, vol. 5, 1998, pp. 57-60; online at <https://philpapers.org/rec/GODTNR>.

[75] Abū Ḥāmid Ghazzālī.

[76] Aminrazavi, loc. cit. See, esp., al-Ghazali’s Tahāfut al-Falāsifa (“The Incoherence of the Philosophers”).

[77] Aminrazavi, loc. cit.

[78] One writer comments, however: “In time, al-Ghazali’s ideas became the dominant mode of thought for the Muslim civilization.” Ziauddin Sardar and Zafar Abbas Malik, Introducing Islam: A Graphic Guide, London: Icon, 2009, p. 91.

[79] Alternatively, the “Book of Creation.”

[80] E.g.: “Probably the most important Platonic notion to find its way into Kabbalistic thought is the doctrine of forms or ideas. … In Sefer Yetzirah, the Sefirot are introduced as archetypal, numerical, or ideational elements, a Kabbalistic translation of or equivalent to the Platonic ideas.” Sanford L. Drob, “Plato and the Kabbalah,” The Lurianic Kabbalah, website, 2001, <http://www.newkabbalah.com/plato.html>. Cf. Drob, Kabbalistic Visions, London: Routledge, 2023.

[81] As well as Gnosticism.

[82] ““The collection of compositions known as Midrash ha-Ne’elam (literally the ‘hidden midrash’) is considered the earliest section of the Zohar.” Pinchas Giller, Reading the Zohar: The Sacred Text of the Kabbalah, Oxford and New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 2001, p. 6, <https://books.google.com/books?id=qloL-PJdtzYC>.

[83] “...Its mysticism seems to have its origins in Neoplatonism, as well as mystical speculations on the power of numbers and the letters of the Hebrew alphabet.” Giller, loc. cit.

[84] Or Psellos.

[85] Or Italos.

[86]The Encyclopædia Britannica reports that a sort of Platonic Academy was reconstituted: “...in Constantinople in the 11th and 12th centuries under the successive leadership of such figures as Michael Psellus, ...; his student John Italus; Michael, the archbishop of Ephesus; and Eustratius, the metropolitan of Nicæa.” “Aristotelianism,” loc. cit.

[87]Also sometimes called Plethon, he was Supposedly born George Gemistus (or Gemistos).

[88]See “Giovanni Pico della Mirandola,” New World Encyclopedia, <https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Giovanni_Pico_della_Mirandola>.

[89]See Frances Yates, The Occult Philosophy in the Elizabethan Age, London: Routledge, 2010.

[90]An article on eLibrary.net states: “Henry More (1614-1687) was the great-grandson of the martyred English chancellor, Sir Thomas More.” “The Cambridge Platonists,” <https://ebrary.net/5078/philosophy/cambridge_platonists>. The Cambridge Platoninsts included lesser lights such Ralph Cudworth (1617-1688), Benjamin Whichcote (1609-1683), John Smith (1616-1652), Nathaniel Culverwel (1618-1651), and, depending on the list, several others. For instance, in his article “Cambridge Platonists,” (Robert Audi, ed., The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy, New York: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1995, p. 100), Alan Gabbey also mentions Simon Patrick (1625-1707), Bishop George Rust (d. 1670), Peter Sterry (1613-1672), and John Worthington (1618-1671).

[91] E.g., they flew under the banner of the phrase Ad Fontes, meaning “back to the fountain” – i.e., skip over Scholastic theologians consult the Bible and Greco-Roman sources directly.

[92] See, e.g., Stanford E. Lehmberg, “Sir Thomas More’s Life of Pico della Mirandola,” Studies in the Renaissance, vol. 3, Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press,1956, pp. 61-74, <https://doi.org/10.2307/2857101> and <https://www.jstor.org/stable/2857101>.

[93] Sometimes, this is referred to by the obscure – and hard-to-pronounce – Latin phrase Tabula Smaragdina.

[94]Lazzarelli was a devotee of Giovanni Mercurio da Correggio (1380-1416). There’s an extraordinary story that claims Giovanni da Correggio once wandered up to the altar in a church, ostensibly claiming to be something like a composite of the Hermetic “Poimandres” and Jesus Christ. He is supposed to have done this in the city of Rome ...in the middle of a religious service in 1484 ...on Palm Sunday, no less which – if you’re unaware – is an important Christian celebration that is timed for one week before the high holy day of Easter. (It’s not entirely clear whether the event actually occurred at all. Assuming it did happen – and at a place of importance – it may have been the Cathedral of St. John Lateran. Some online sources [see, e.g., “Giovanni Mercurio da Correggio,” Wikipedia, Dec. 29, 2021, <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giovanni_Mercurio_da_Correggio#Palm_Sunday_1484>] say that the church was Saint Peter’s Basilica. But, construction on Saint Peter’s – properly so-called – wasn’t started until sometime in 1506. Though, possibly, the reference was supposed to be to the “Constantinian Basilica” upon which Saint Peter’s was built.)

[95]It is noteworthy that Bruno traveled to England where he was said to have interacted with the poet Philip Sidney (1554-1586); Sidney was a friend of Dee’s.

[96]He himself had been partially molded by the Islamic thinker Averroës (1126-1198).